“I have lectured in parlors fourteen years,” Mary Baker Eddy commented to one of her students in the late 1870s. “God calls me now to go before the people in a wider sense.”1 Obeying that call required a time-consuming weekly commute.

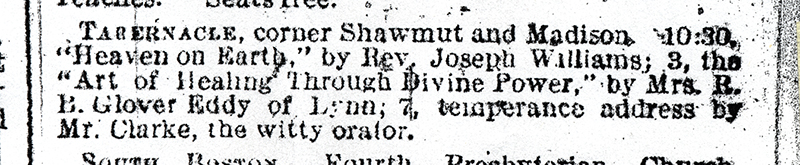

In November 1878, Mrs. Eddy announced the first of a series of Sunday afternoon lectures in Boston, the intellectual capital of the country at that time. The topic for the first lecture would be: “The Art of Healing Through Divine Power.” It was to be given in the rented vestry room of the Free Tabernacle Baptist Church in Boston’s South End neighborhood.

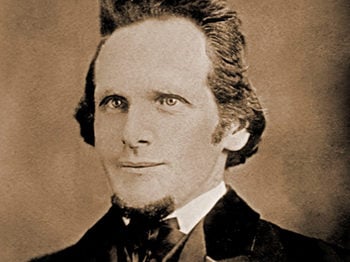

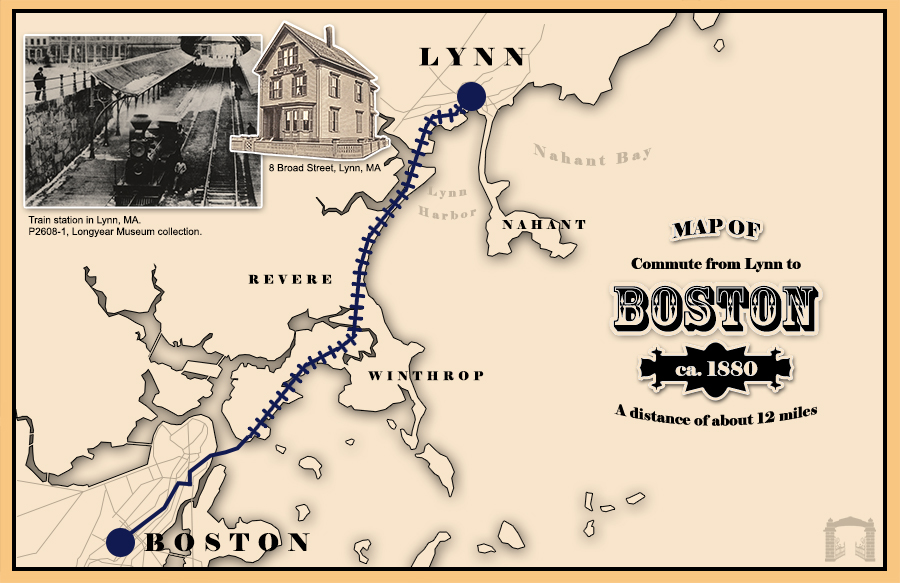

At that time, Mrs. Eddy and her husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy, were living not in Boston, but in Lynn, the great shoe-manufacturing town across Boston Harbor and some twelve miles to the north as the crow flies. Commuting to Boston and home again would test their scheduling ability and their stamina.

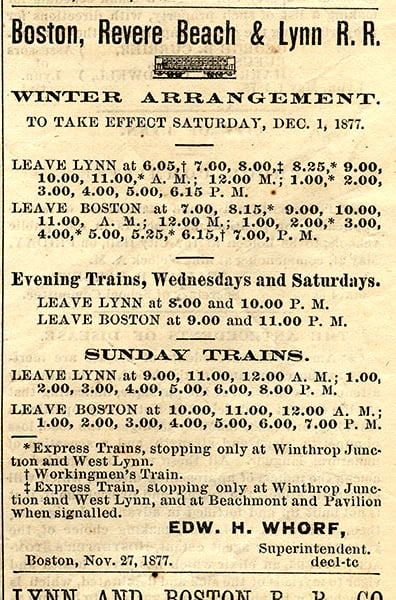

On Sunday mornings the Eddys might well have started out on a horse-drawn trolley, on rails that ran past their Broad Street home down the dirt road to one of the rail terminals in central Lynn. There they would board a train (perhaps the Eastern Railroad or the Boston & Maine, or perhaps the new Boston, Revere Beach, and Lynn narrow-gauge line) and travel south along the shoreline to East Boston. Transferring to a ferry, they would cross the harbor to Atlantic Avenue on the Boston side. A short walk would bring them to Haymarket Square in the city’s North End, where they would board another horse-drawn trolley car for the jolting ride far out along Shawmut Avenue. At the end of the line, they would walk the rest of the way to the church in the South End. The round-trip journey could take three or four hours.

The Eddys’ commute — a mix of horses and steam engines, dirt roads, docks, and rails — may sound quaintly old-fashioned today. But at that time, such travel was in step with up-to-date modernity, including the newest modes of transportation and communication. A decade or two earlier, the trip to Boston might have taken most of a day. The trolleys, train lines, and trestles, even the district of Boston that was their destination, were all new in the 1870s.

Even with those modern conveniences, the route from Lynn to Boston’s Back Bay and home again might have challenged the hardiest traveler. What’s remarkable is that this grueling round-trip, plus the hours of preparation and lecturing, were being undertaken by a woman who, ten years earlier, had been weak, sickly, and close to death — and by a man who had been nearly incapacitated by his ailments just a couple of years previously. The couple’s ability to complete these weekly excursions was a testament to the Christian Science healings that had changed their lives.

Arriving at the vestry room, the Eddys and some local helpers had to clean up the hall, arrange chairs, and set out literature and programs.

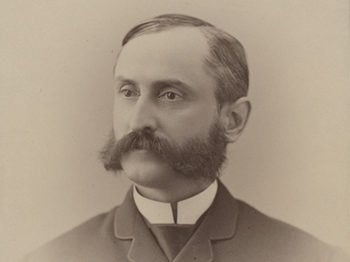

As people arrived for the lecture, Gilbert Eddy, nicely attired in his Prince Albert frock coat, welcomed them at the door.2 Mrs. Eddy, wearing a graceful velvet gown, conducted the proceedings. Following her talk, she patiently answered questions and gratefully listened to testimonies of healing.

In late November, Mrs. Eddy held a Thanksgiving service. After her sermon, members of the congregation broke into spontaneous expressions of thanks for the benefits they had received from her teaching and textbook. Her student Clara Choate recalled: “Some wonderful healing was reported. Mrs. Frothingham said she had not come into Christian Science because of any physical cure… but because her spiritual insight of God was made clearer and more practical.”3

At the end of the day, Clara accompanied the Eddys on their long ride home. In later years, she remarked on her teacher’s forward-looking energy: “All the way home to Lynn Mrs. Eddy talked of widening the avenues for the work in Christian Science… larger places to worship in, or more students in the field, or more editions of the textbook, always so confident, expectant, and prophetic.”4

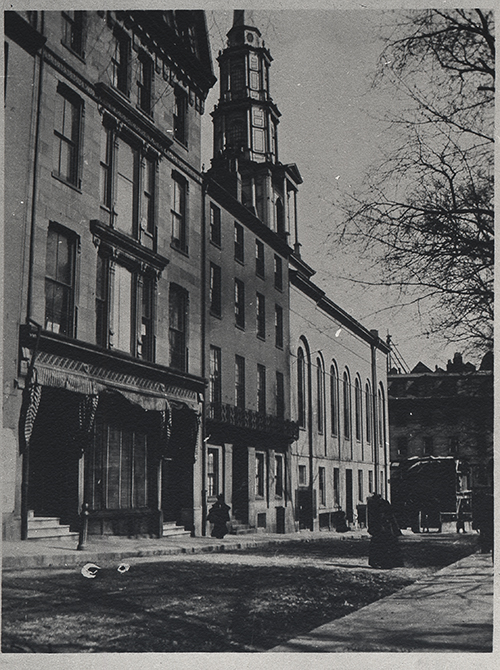

These were modest-size gatherings at the start. But each week, as word spread, Mary Baker Eddy’s inspiring lectures, along with reports of healings, attracted more and more attention. The meetings soon outgrew the vestry room of the Free Tabernacle Baptist Church. In February 1879, they moved to the larger Fraternity Hall in the Parker Memorial Building closer to downtown. Mrs. Eddy’s commute continued, week-in, week-out.

Still, her larger vision of a church of her own was not much more realized from when she had noted a few years earlier: “[W]e have not a pulpit from which to explain how Christianity heals the sick….”5

In April 1879, her student association voted to organize a Christian Scientists’ church, and in August the church charter gave Boston as its location. Mrs. Eddy reluctantly decided to leave her beloved home in Lynn and rent furnished rooms in Boston. By November, the Sunday afternoon services of the Church of Christ (Scientist) had to move to the spacious Hawthorne Rooms on Park Street, just down the hill from the gold-domed Massachusetts state capital.

In 1881, Mrs. Eddy chartered the Massachusetts Metaphysical College and returned to Lynn to teach classes at her home there. But she now felt called to “go before the people” in an even wider sense. Going forward, she would re-establish her movement’s school and headquarters in Boston. In January 1882, the Eddys boarded a train for the Lynn-to-Boston run for the last time. The arduous commute from Lynn was over, signaling the beginning of a new chapter in her life that would bring her message to New York, Chicago, the American West, and the world.