WHEN MRS. EDDY WAS LIVING AT 23 PARADISE ROAD, SWAMPSCOTT, in 1866, she experienced a remarkable recovery from an accident, which she regarded so important that she referred to it several times in her writings as the event which led directly to her discovery of Christian Science. “In the year 1866,” she wrote in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (p. 107), “I discovered the Christ Science or divine laws of Life, Truth, and Love, and named my discovery Christian Science. God had been graciously preparing me during many years for the reception of this final revelation of the absolute divine Principle of scientific mental healing.” Her works Miscellaneous Writings, p. 24, and Retrospection and Introspection, pp. 24 and 26, are also of interest in this connection.

Because of the significance attached to this event by Mrs. Eddy, and because countless lives have been regenerated through the discovery of Christian Science, Longyear Foundation is preserving for future generations the house in which Mrs. Eddy lived at this time. As the years go by, it will be valuable historical evidence of the life of the discoverer and founder of Christian Science. From Mrs. Eddy’s writings, from letters, documents, newspapers, and reliable records of her life, this account of the months spent by her at 23 Paradise Road has been written.

The “apartment was light and airy”

In the fall of 1865 Mrs. Eddy, then Mrs. Patterson, and her husband, Dr. Patterson, rented an apartment on the second floor of the home of Mr. and Mrs. Armenius Newhall, at 23 Paradise Court, Swampscott, Massachusetts. Paradise Road was then called Paradise Court….

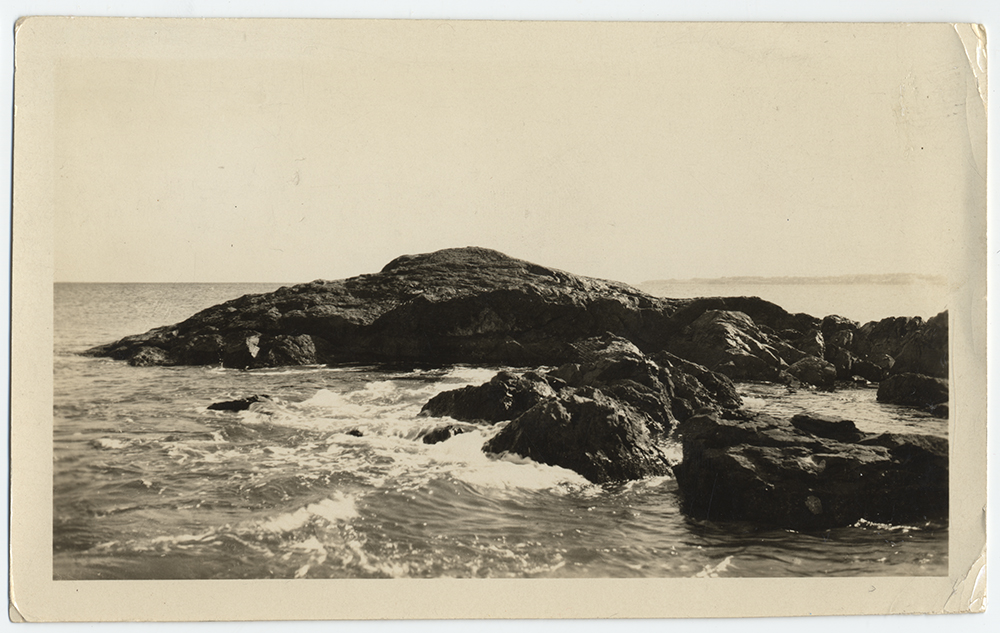

Swampscott was then a quiet little fishing village, adjoining Lynn. The shore was dotted with fishing barges. The Newhall home was very pleasantly situated, not far from the ocean, with plenty of open land around it, two and a half acres belonging to the Newhalls. Besides the two-story house with piazzas on the front and south side, a stable and observatory were on the grounds. The house was well built and substantial, practically as it is today.

The Newhalls were well-to-do, refined people. The Lynn Directory listed Mr. Newhall as a fish merchant and a dealer in provisions. Their home was comfortably furnished. The Pattersons’ apartment was probably furnished partly by them and partly by the Newhalls.

This second-story apartment of four rooms was light and airy. Its windows looked out on a wide, sloping lawn, near the edge of which was a fountain shaded by a willow, on an orchard with orderly rows of pear and apple trees, and on a garden well-stocked with strawberry plants, currant and gooseberry bushes…. There was a wide sweep of sky which Mrs. Patterson loved to watch. She thought the Swampscott skies beautifully blue and wonderful in their changing moods and colors. From her parlor windows she admired the brilliant sunsets and the magic beauty of moonlight nights. She was most appreciative of nature, and loved to go down to the shore, look out on the wide expanse of ocean, hear the pounding of the surf, and spend time in quiet contemplation. In the winter, when the wind howled about the house and the snow was piled high, she fed the snow birds on her window sill.

Mrs. Patterson was forty-four years old when she moved to Swampscott. She was in better health than she had been for many years. Although she rejoiced over her increased activity and her new interests, she was often sad, for her marriage with Dr. Patterson was not proving a happy one. He was a skillful dentist, and well-liked by people in general because of his jovial disposition, but he was temperamentally unable to apply himself steadily to his profession, and was always in straitened circumstances. Their interests drifted farther and farther apart…. And now, in the fall of 1865, her father, Mark Baker, passed on. There were moments when she felt utterly alone, and she turned to God, as she always had, for comfort and strength.

“In her quiet way she commanded attention”

She was a fine looking woman, graceful and slender, with deep blue-gray eyes and a fair skin. Her brown hair was arranged in curls about her face as was the fashion of the day. She dressed well and becomingly in spite of her limited means, usually wearing black with violet or pale rose trimmings….

She readily made friends in Lynn and in Swampscott. In her quiet way she commanded attention. When she talked, and was interested in her subject, her eyes glowed, and color came to her cheeks. She was a good conversationalist and had a winning, kindly manner…. Few women allowed their thoughts to stray far beyond the four walls of their homes, few ventured to speak in public, few wrote for publication. Mrs. Patterson did all these things naturally, without feeling that she was defying the conventions. She was always interested in the world about her. These were the difficult years of reconstruction after the Civil War…. Two of Mrs. Patterson’s poems, written and published at this time, “To the Old Year 1865” and “Our National Thanksgiving Hymn,” show that she was thinking over these matters….

The North was adjusting itself once more to peacetime pursuits, and interest was reviving in education, in Lyceum lectures on cultural subjects, in religion and temperance. Vassar College, the first fully endowed college for women offering courses on a par with those at Harvard and Yale, opened its doors in the fall of 1865. This was an important step in the recognition of the mental ability of women.

Temperance societies were recruiting new members. Dr. and Mrs. Patterson had joined the Linwood Lodge of Good Templars, a temperance organization in Lynn, which worked for prohibition legislation and total abstinence. This Lodge was first organized by men, but soon a few women formed an auxiliary group, called the Legion of Honor. Women had asserted their interest in temperance in the eighteen-fifties, and their persistent efforts to share in the work for the cause had borne fruit by 1866. Nevertheless, women who were interested in causes were greatly in the minority, and were still regarded by the general public as queer and unfeminine, and as straying out of their sphere. Mrs. Patterson was an active member of the Legion of Honor of the Linwood Lodge, and served for a time as presiding officer. She was often called upon to speak or to read, and did so with ease and effectiveness.

“She often sat for hours, writing”

She delighted in expressing her ideas in writing. As a small child she had the ambition to write a book. Before she was twenty she began sending short articles and poems to the newspapers; and by 1865 had written with considerable success for New Hampshire, Portland, and Lynn newspapers, for the Connecticut Odd Fellow, and the Freemason’s Monthly Magazine. In the I.O.O.F. Covenant, she had published a short story, “Emma Clinton, or a Tale of the Frontiers.” Her poems had been printed in Godey’s Lady’s Book — an honor for a woman in those days; and two were reprinted in 1850 in Gems for You, one of the many gift books then so popular. She had even had a request for an article in 1864 from The Independent — that popular New York weekly edited by Theodore Tilton. Now, in Swampscott, she devoted much of her time to writing. In the fall, while the weather was still fine, she often sat for hours thinking and writing under the willow by the fountain. She wrote short, chatty articles and poems for the Lynn Weekly Reporter in the flowery style of that period….

She attended the Congregational Church in Swampscott, and characterized the sermons of her pastor, the Reverend Jonas B. Clark, as strong, clear, and logical.

To watch the moonbeams on the wave…

then to catch an occasional glimpse,

in another survey of thought,

of one’s spiritual self —

to see what shadows we are

and what shadows we pursue.

From an untitled article by Mary M. Patterson (Mary Baker Eddy)

The Lynn Reporter, April 4, 1866.

“Good friends and near neighbors”

Two of her fellow church-members, Mrs. Mary Wheeler and Mrs. Carrie Millet, were good friends and near neighbors. Among the most mentally congenial of her friends at this time were Mary P. Ellis and her son, Fred, who was in charge of the grammar school. Mrs. Patterson spent many happy evenings with them in stimulating conversation, and later, when she was in need of a home, they took her in.1

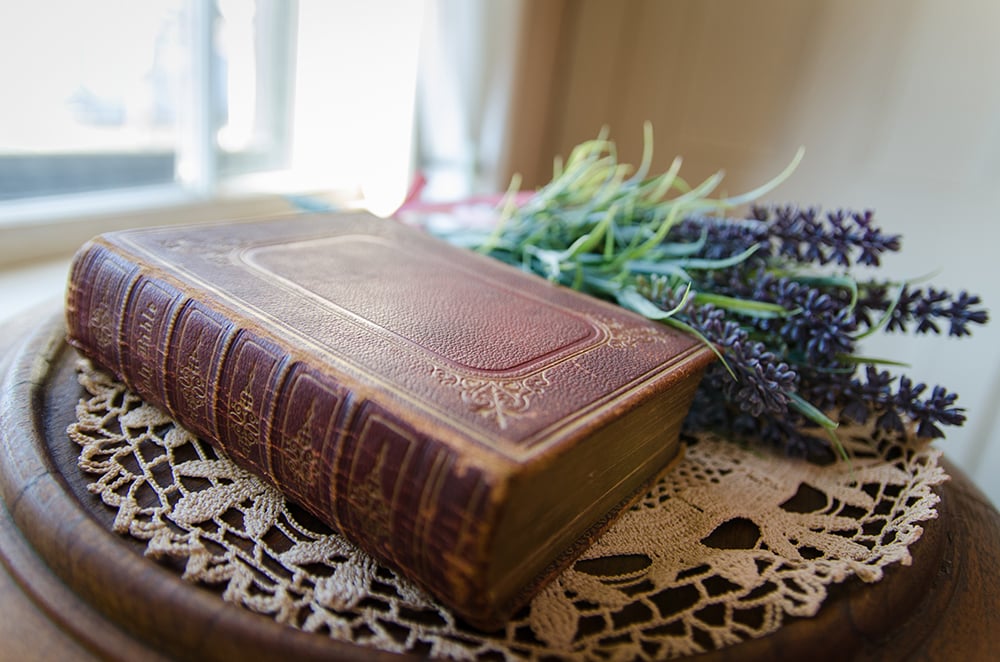

The home of Hannah and Thomas Phillips in Lynn was also a mental refuge. They were Quakers, intelligent and understanding. Mr. Phillips had been a manufacturer of shoe findings. He was more sympathetic to her religious ideas than the rest of the family, although his son-in-law, George Oliver, said he liked nothing better than a talk with Mrs. Patterson, and preferred it to putting through a business deal. Mrs. Patterson dearly loved the aged grandmother of the family, and often sat hand in hand with her on the sofa, talking about God and the Bible. She was impressed by the silent prayer of the Quakers before meals.

Charles and Abby Winslow, relatives of the Phillips, were also good friends, and later she healed Mrs. Winslow, who for years had been unable to walk. Mr. Winslow was a wealthy shoe manufacturer.2

Mrs. Patterson was also very much at home with Rebecca and Ira Brown, who lived on Essex Street, Lynn. They were well-to-do, and owned considerable property. Mr. Brown was in the lumber business. Whenever she came to call, and could stay for luncheon or dinner, Mrs. Brown immediately told the cook to put the potatoes in the oven so that Mrs. Patterson could have them the way she liked them best. Their ten-year-old daughter, Arietta, always enjoyed her visits and thought her full of fun. She liked nothing better than to get Mrs. Patterson comfortably seated, and then to comb her hair and wind her curls on a round stick.

Mrs. Patterson talked very freely to all her friends about religion, which meant so much to her — not about a religion of creeds or ceremonies, but of personal relationship with God which must be expressed in daily life. Her years of invalidism had led her to search for a connection between religion and healing, and she tried to work this out in practice whenever she found anyone at all receptive to her ideas. Then came an experience which confirmed her hopes and made her continue her search with renewed zeal.

“Her friends hurried to her bedside”

On February 1, 1866, in the evening, while she was on her way to her Lodge meeting with friends, she slipped and fell on the icy sidewalk in front of the shoe factory of Samuel M. Bubier, on the corner of Market and Oxford Streets, Lynn, and was severely injured.

She was carried across the street into the Bubier home, and Dr. Alvin M. Cushing, a well-known homeopathic physician of Lynn, was called to attend her. According to Dr. Cushing, she was very nervous, semi-conscious, and semi-hysterical. He left medicine to quiet her. The next morning, when he called, she complained of severe pain but insisted on going home, and he arranged to have her taken to Swampscott wrapped in blankets and robes in a long sleigh.

Dr. Patterson was away from home at the time, in New Hampshire, either on dental business or lecturing on his Civil War prison experiences, and her friends telegraphed him to return.

The Lynn Weekly Reporter of February 3, 1866, carried the following account of the accident:

Mrs. Mary M. Patterson, of Swampscott, fell upon the ice near the corner of Market and Oxford Streets, on Thursday evening, and was severely injured. She was taken up in an insensible condition, and carried to the residence of S. M. Bubier, Esq., near by, where she was kindly cared for during the night. Dr. Cushing, who was called, found her injuries to be internal, and of a very serious nature, inducing spasms and intense suffering. She was removed to her home in Swampscott yesterday afternoon, though in a very critical condition.

The news of her accident travelled quickly among her friends, and some of them at once hurried over to her bedside to see what they could do to help her. Mrs. Carrie Millet and Mrs. Mary Wheeler spent the night with her, and the next morning sent the milkman, George Newhall, to tell the Reverend Jonas B. Clark of her condition.

“She told them she was going to walk”

Sunday morning Mr. Brown drove his wife and daughter to Swampscott to see her. Mrs. Patterson was in bed, but as they left she told them she was going to walk. They thought it impossible, but when they came in later to bring her some chicken for her supper, they found her in the parlor. She had walked in, as she said she would.

As she lay in bed, reading her Bible, she turned to the record of Jesus’ healing of the palsied man in the ninth chapter of Matthew, and glimpsed a new meaning in that story. In a flash of spiritual understanding she realized that at the basis of Jesus’ healing was a principle which was applicable to her then and there, and she felt she was free. She got up from her bed and went into the parlor where her friends were gathered. They were amazed. Some thought it a miracle. Others were anxious for her, and feared she was overdoing. She could not explain to them then what had happened except that she had been healed by prayer, but when she was by herself again, away from their doubts and hampering thoughts, she felt stronger, and was very sure that out of this moment of spiritual illumination she would glean something of great value.

As she explained it later in Miscellaneous Writings (p. 24), “That short experience included a glimpse of the great fact that I have since tried to make plain to others, namely, Life in and of Spirit; this Life being the sole reality of existence.”

But she did not at once comprehend all that this experience implied.3 A full understanding required years of growth. For the next few weeks, while she remained at 23 Paradise Road, she struggled to hold to the truth which she had glimpsed. In March, when the Newhalls offered their house for sale, she was obliged to leave this spot which she loved and move to Lynn. She described it appreciatively in an article for the Lynn Weekly Reporter, and this not only was a help to the Newhalls, but has been of great value in later years in furnishing details about the months she spent in Swampscott.

During the next few years she faced poverty, loneliness, and disillusionment in her relationship with her family and friends. But the spiritual illumination which came to her thought on the Sunday after her fall, stood out as a guiding light, and led her gradually into a clear understanding of spiritual healing based on the divine Principle, God. This system of healing she has explained and made available to all in the textbook of Christian Science, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.