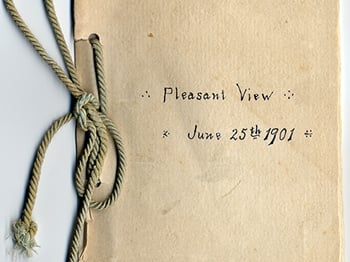

A curious anomaly exists within Mary Baker Eddy’s work Miscellaneous Writings: 1883-1896. True to its title, its contents include articles published within that date range — except for one: Mrs. Eddy’s Fourth of July address delivered at Pleasant View in 1897, a date that is clearly outside the time frame of collected materials.

This 1897 date is not a misprint; several months after the publication of Miscellaneous Writings, Mrs. Eddy did host a memorable Independence Day celebration in which she and others addressed 2,500 Christian Scientists.1 Unique in its own right, this occasion set a precedent for future gatherings at Pleasant View, and in early 1898, the text of Mrs. Eddy’s address appeared in Miscellaneous Writings.

The resulting anomaly in dates, whether unnoticed at the time or purposefully untouched, nevertheless remains today, pointing our gaze towards the subject at hand: the 1897 visit to Pleasant View, momentous for its precedent, participants, incidents, metaphysics — memorable indeed “in the annals of Christian Science.”2 And yet, for all its lasting import, the gathering came about quite spontaneously.

The Invitation at Communion

Sunday, July 4, 1897, was a special occasion in The Mother Church. It was the Fourth of July, but it was also Communion Sunday, and there were over 1,400 new Church members to be admitted. Surely many hoped that Mary Baker Eddy herself might make an appearance, but this was not to be.3 Instead, at the close of each service, just before the benediction, First Reader Septimus J. Hanna read aloud from the desk an invitation from Mrs. Eddy:

I invite you, one and all, to Pleasant View, Concord, N.H., on July 5, at 12:30 PM, if you would enjoy so long a trip for so small a purpose as simply seeing Mother.4

A privileged few had known this announcement was coming, while others may have heard rumors, but to the majority of those seated in the pews that day, this was an unexpected yet extraordinary opportunity.5 Whatever plans there had been for the next day’s federal holiday, perhaps an Independence Day parade or even a return trip home, were forgotten or rescheduled.6 This was not to be missed.

The historical evidence indicates that the event came together quickly. Having decided not to attend Communion, Mrs. Eddy must have recognized the opportunity afforded by two factors: the swell of Christian Scientists visiting Boston and the holiday on Monday.7 It gave just enough time for a trek to New Hampshire. In any case, the plans for the visit were set in motion less than a week before July 5.

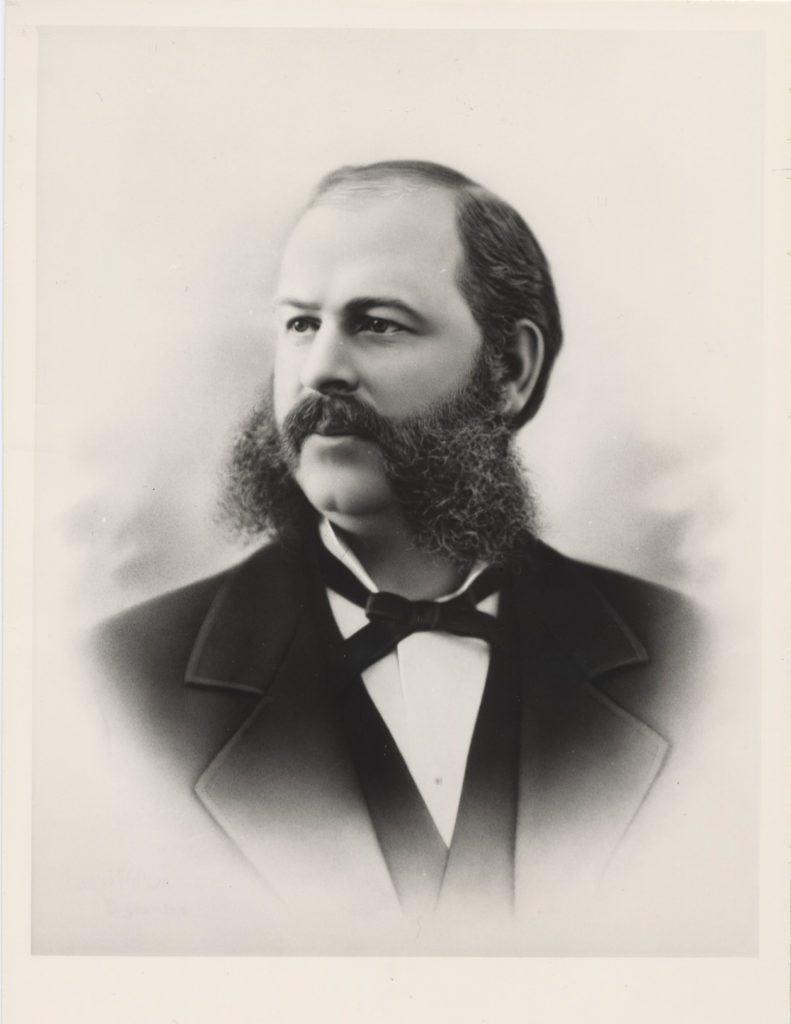

In Boston, Septimus Hanna was one of the first to know, when he received a telegram from Mrs. Eddy the previous Wednesday.8 He was instructed to read the invitation at the Communion services and to ask Edward P. Bates to secure from the railroad sufficient travel arrangements. Given the short notice, this was a massive undertaking, but true to his reputation, Bates pulled off the logistical feat.9 By 9:30 AM on Monday, July 5, about 1,200 Christian Scientists were ticketed, seated, and on their way to Concord, New Hampshire.10

At Pleasant View

It was a hot day. On the shaded porch at Pleasant View, the mercury showed 102 degrees.11 There was lemonade available in front of the barn, and some people scooped water from the fountain with tin cups.12 But by all accounts, the crowd that had now gathered before the handsome home’s front façade was impressively unfazed.13 Including those from Boston, about 2,500 people were now waiting in the yard.

Above them, a solitary American flag floated towards the east. Before them, a group of honored guests found seats beneath the shade of the porte cochere. Distinctly centered was a haircloth armchair with a card pinned to its front that read “Mother.”14

Inside, Edward Bates was cleaning up. Having overseen the successful transportation of 1,200 people 70 miles to Pleasant View, he had acquired some dust and dirt. So he was surprised when Mrs. Eddy asked him to escort and introduce her to the crowd waiting outside. He of course complied, and with her hand on his arm, they stepped through the front door at 1:00 PM to a chorus of three welcoming cheers.15

The program was a straightforward affair. There were nine notable speakers, including Mary Baker Eddy, three former clergymen, several Civil War veterans, and two who were not Christian Scientists. Together the speeches lasted roughly an hour, touching on patriotic themes and Christian Science, as well as sharing a common reverence for Mrs. Eddy. Hers of course was the most memorable address of the day, but for her it was a special treat to hear from the others, at least two of whom she had never met in person before.16

In fact, the event essentially debuted several up-and-coming Christian Scientists, namely William P. McKenzie, George Tomkins, and Irving C.Tomlinson. There were other Scientists that spoke that day, such as Hanna, but they were already well established within the movement. These three, on the other hand, were relatively new, and owing to their promising potential, soon found themselves installed in significant Church positions. Their Pleasant View speeches, then, may be seen as the beginning of their Christian Science careers.

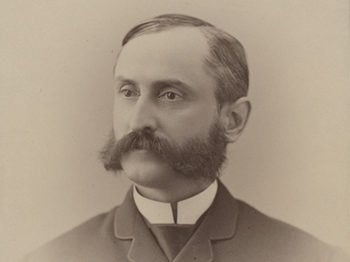

The University Professor | At thirty-six years old, William P. McKenzie had been a dedicated Christian Scientist for several years. A First Member since 1894, two years later he answered the request to serve on the Bible Lesson Committee, work for which he was well suited, given his education in theology and his years as a professor of both English and rhetoric. His work in this capacity must have showed promise, because Mrs. Eddy named him as a speaker for the Pleasant View occasion, though she had never heard him address the public before.17

As late as July 3, though, it was unclear whether McKenzie would actually have the opportunity to speak.18 He ultimately did, and he spoke well. Highlighting watershed moments of American liberation, he proclaimed:

We have the universal tongue, the prepared country,

the Leader whom God appointed. Shall this

prepared people count anything as loss that they

may have to give up in laboring for the independence

— the liberty — of the sons of God?19

Several months later, Mrs. Eddy wrote McKenzie and reiterated how impressed she was with his remarks.20 His proven devotion to the Church, coupled with his demonstrated ability to communicate clearly, marked him for a future within the movement. Less than a year later, McKenzie was named to the Board of Lectureship as one of its first five members, a post he would hold until 1915.

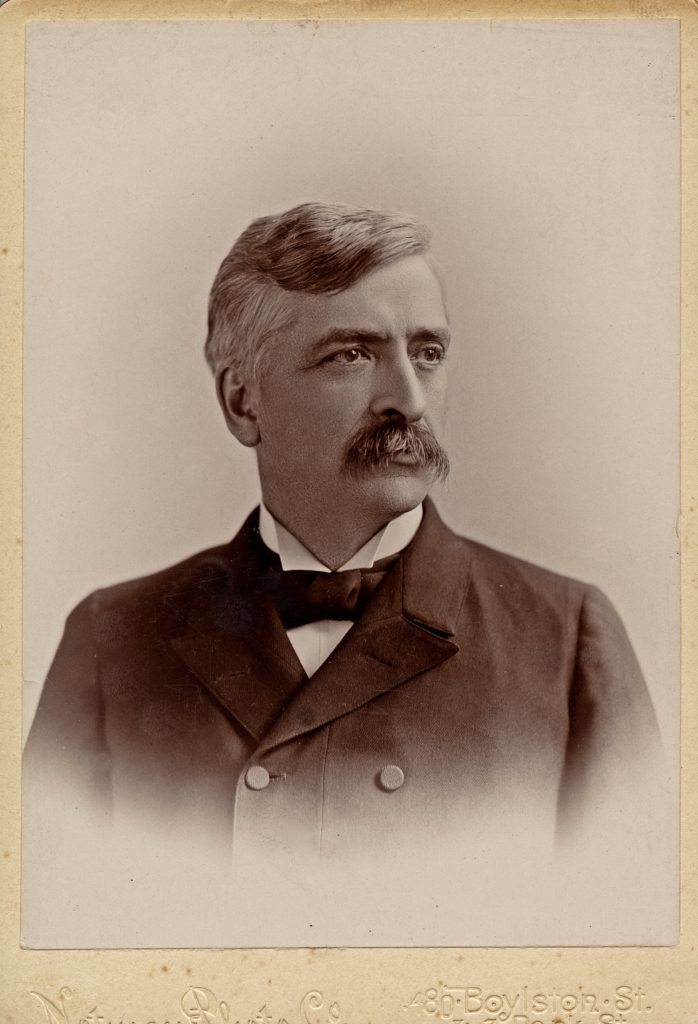

The Baptist Minister | With a seat among the honored guests, the Reverend George Tomkins, DD, must have wondered at the turn of events that had brought him to Pleasant View. An Englishman with an intriguing personal history, Tomkins had only begun his serious study of Christian Science the past December.21 Involved for several years beforehand with the Baptist movement in New York, he navigated his own “second-hand prejudice” against Christian Science and became a student at Laura Lathrop’s New York Christian Science Institute.22

In May, Tomkins’s first article in The Christian Science Journal appeared: “What Made a Baptist Minister a Christian Scientist.”23 Mrs. Eddy wrote him, praising the article as excellent and calling its author a “light to those in the darkness.”24 She also expressed interest in a personal meeting at Pleasant View during the upcoming Communion season.

So on Thursday, July 1, Tomkins took an evening boat from New York to Boston. On Sunday, he became one of the 1,400 newly admitted members to The Mother Church; it was after this Communion service that he received a special message from Mrs. Eddy, asking him to be a speaker at Pleasant View the next day.25

Standing before the 2,500, Tomkins spoke earnestly about his spiritual resurrection and how he hoped to be counted by posterity as an early Christian Scientist.26 After the program, Mrs. Eddy and Tomkins met inside for a brief but memorable conversation, a favor that he considered to be “one of the very greatest privileges of [his] life.”27

With a purposeful zeal Tomkins left Pleasant View. His healing practice quickly flourished, which he detailed in correspondence with Mrs. Eddy. These promising reports, and his conduct upon the platform, must have distinguished Tomkins, leading to his appointment to the Board of Lectureship in 1898. This was a remarkable advancement, given it had been just one year since he first began his study of Christian Science.

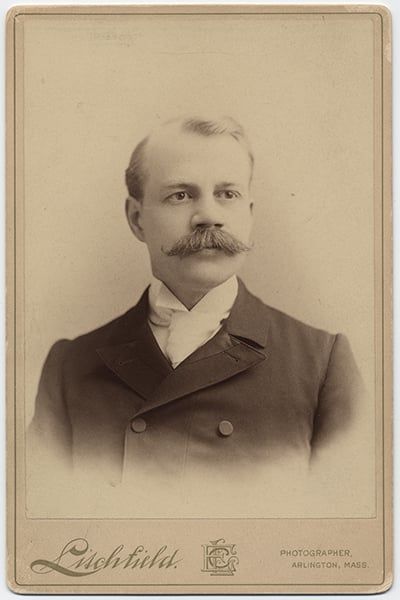

The Universalist Preacher | To Irving C. Tomlinson, the visit to Pleasant View marked the beginning of a personal transformation in which he was ushered “into a new world.”28 The thirty-seven year old had close to a decade of preaching experience in Universalist churches, yet he still marveled at his opportunity to speak before Mrs. Eddy just a day after his admission to The Mother Church.

Tomlinson took Primary class instruction in 1896 from Flavia Knapp, and in 1897 it was through her that he received his special invitation to Pleasant View.29 It is unclear what exactly propelled him to Mrs. Eddy’s selection — perhaps his first article in the June Journal30 — but nevertheless, Tomlinson found himself invited to speak.

Pervading the entire Pleasant View affair was an atmosphere of “reverence and holiness” that struck him deeply.31 Aware of his only recent awakening to Christian Science, his remarks were prepared with guidance from Flavia Knapp. It was with childlike humility that he spoke to his new Church family. “Loyalty,” he said, “is the child of Love, and the child best shows its loyalty to Mother by labor for her cause. The pilgrimage to Concord means labor for concord.”32 He continued with a loving tribute to Mrs. Eddy: “… here in this fair spot, symbol of universal peace and harmony, we dedicate to thee and to the Cause, with loving hearts and loyal hands, all we are, all we have, and all we hope to be.”33

Mrs. Eddy granted Tomlinson a brief interview after the program. To him, she radiated freedom, while to her he was a sign of hope for the Cause. She recalled this impression in a letter to him: “From my first moments with you I have felt that you had come to help us and weighed in the balance would not be found wanting.”34 Like McKenzie and Tomkins, Tomlinson too was named to the Board of Lectureship in 1898, which was the first of many posts he would hold in a life dedicated to Christian Science.

The Address

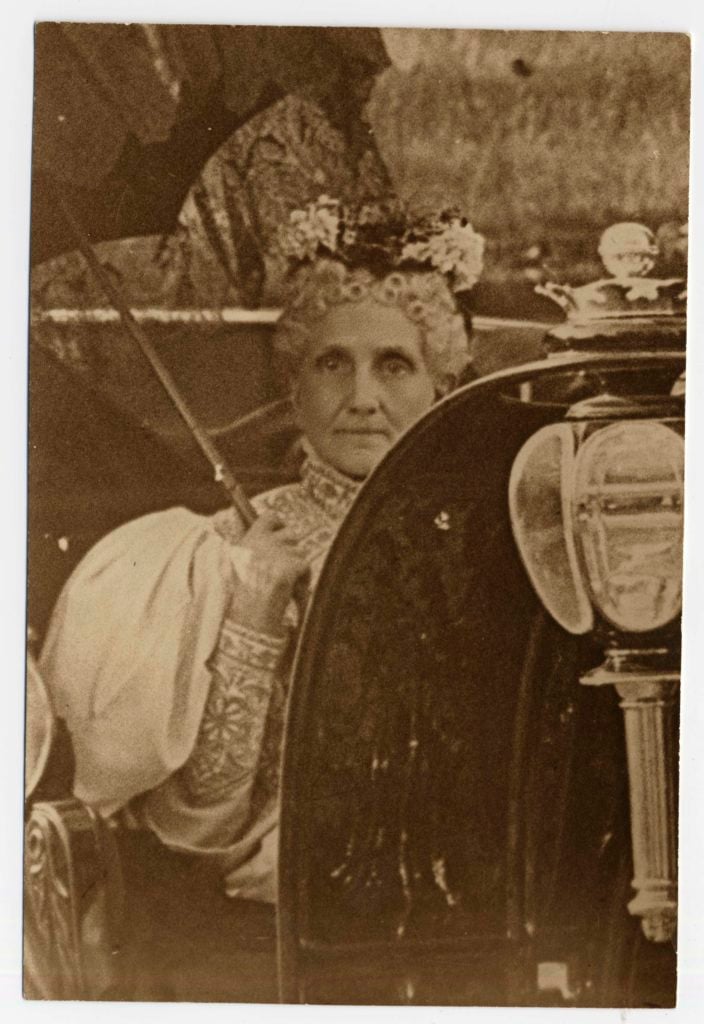

Mary Baker Eddy’s address from the platform was clearly the most prominent feature of the day’s program. Though all spoke well, it was for her that all had come, and it was her that they remembered most. The Boston Herald called Mrs. Eddy the “picture of health and energy,” while the Boston Globe noted her “straight as an arrow” posture, yet “delicate and tender” composure.35 Upon her dress of purple silk she wore a diamond cross and a ruby badge, the latter an ornament of the Daughters of the American Revolution. A bonnet over her silver-white hair completed the ensemble. Mrs. Eddy had two more accessories that apparently took some by surprise: a black fan in her hand and a pair of eyeglasses that hung from a gold pin on her dress.36 She used the fan from time to time, but the consensus was that Mrs. Eddy seemed least affected by the heat.37 As for the glasses, she did not use them. Significantly though, Mrs. Eddy did read her address from a manuscript, rather than speak extemporaneously.38 This reinforces the fact that she did not need her glasses on the occasion, but also highlights the interesting point that she had prepared her remarks.

The address began:

My beloved brethren, who have come all the way from the Pacific to the Atlantic shore, from the Palmetto to the Pine Tree State, I greet you; my hand may not touch yours to-day, but my heart will with tenderness untalkable.39

Incorporating the day’s theme, she spoke about the inalienable liberty of the sons of God, so radiant in the reality of Christianity, and she emphasized the richness of this inheritance. Moreover, she declared Christian Science to be universal, underscoring its ability to meet the needs of every person in every circumstance, and concluding with the admonition: “if a man findeth, he goeth and selleth all that he hath and buyeth it. Buyeth it!”40

Polished and eloquently delivered, her address belied the quick turnaround time in which she had completed it. Writing to Hanna about its development, she confided, “I had such a fire as never before. So at the last moment prepared an article to read, a thing I have not [done] before in many years.”41 Indicated is a combination of pressures from an unspecified challenge and a shortage of time.

While the particular “fire” she had faced is unclear, it is apparent her address came together just a few days beforehand. However, some of her main ideas and even distinct phrases were developed a number of weeks, or even months, earlier. This can be seen in three Mary Baker Eddy documents, which together with her final published version, form a sequence:

First Undated Handwritten.

Second May 22, 1897 Typewritten.

Third July, 1897 Typewritten.

Fourth July 6, 1897 Published.42

Though the four documents share content similarities, the first and second documents were apparently not written with the Pleasant View occasion in mind. In a distinct shift, the third document introduces new content oriented for a public event. Furthermore, there are substantial differences between this third document and the final fourth version.

Therefore, it can be concluded that while Mrs. Eddy had been developing some key ideas and phrases as early as May, it was not until just a few days before July 5 that she significantly revised and adapted this article for her address. This clarifies Mrs. Eddy’s comment regarding the last-moment nature of her speech, and it also reinforces the quick and spontaneous origin of the event itself.

“For Our Dear Cause”

Her part done, Mrs. Eddy listened intently to the speakers that followed.43 When the program concluded, a line was formed to meet her as she sat beneath the shade of the porch. With 2,500 guests and return trains to catch, each person could have had at most only a few seconds to greet and thank their hostess. There was not sufficient time to shake every hand, and Mrs. Eddy gave priority to strangers over her own students.44

A slight stir was caused by one unfortunate incident. Edward Bates made a statement from the porch regarding some visitors from Kansas City, Missouri. This group had traveled by train for two days to be there, but Bates’s tactless comment essentially told them they had not been invited.45 Mrs. Eddy quickly rose and gracefully qualified his remark by adding that she was nonetheless grateful for their presence.

Later, when this particular group came along in the greeting procession, a touching interaction occurred between some of the children and Mrs. Eddy. The mother of those children, Jessie Cooper, remembered this moment as a testament to Mrs. Eddy’s capacity for love:

I wish I could make the world know what I saw when she looked at those children. It was a revelation to me. I saw, for the first time, the real mother LOVE, and I knew that I did not have it.46

Mrs. Cooper’s newfound sense of Love affected her profoundly, and later that evening she found that a painful boil on the crown of her daughter’s head had disappeared.47 Countless more would remember with fondness the visit to Pleasant View. To locals, it was a remarkable religious pilgrimage. To Christian Scientists, it was an unforgettable opportunity to meet the Leader of their church. To some, such as Irving Tomlinson and Jessie Cooper, it was even a transformative personal experience. In her own words, Mrs. Eddy considered it a “boom for our dear cause.”48

She and others recognized the occasion’s significance, and care was taken to put it on record.49 In the Journal, a lengthy tribute detailed the experience, replacing the usual Communion review.50 Her address also found its way into Miscellaneous Writings, where it can still be read today. Its inclusion remains a curious anomaly with an extraordinary history, elevated by its spiritual message to posterity, and a worthy testament to that memorable Independence Day when a crowd of 2,500 gathered from all points to see and hear and meet Mary Baker Eddy.