The morning of June 25, 1901, was beautiful, noted Concord, New Hampshire’s Daily Patriot, “but exceedingly hot.” By midday, temperatures would hit 90 degrees. The heat didn’t deter visitors to the city that day, however. They descended on Concord by the thousands, streaming from special trains from Boston and thronging the streets.

Mary Baker Eddy had surprised her followers with an unexpected invitation to Pleasant View, her home on the outskirts of New Hampshire’s capitol. Although it had become customary for many Christian Scientists to travel north to Concord to sightsee following the annual Communion service at The Mother Church, the last formal invitation extended by Mrs. Eddy had been four years earlier, in 1897. And so, when word came on that Monday that she would be welcoming visitors at her home the following afternoon, Christian Scientists jumped at the opportunity.

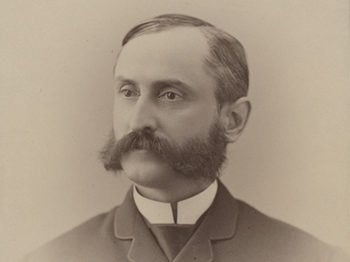

So did a local photographer, one Willis G. C. Kimball, whose pictures of the event would eventually be sold as souvenirs.

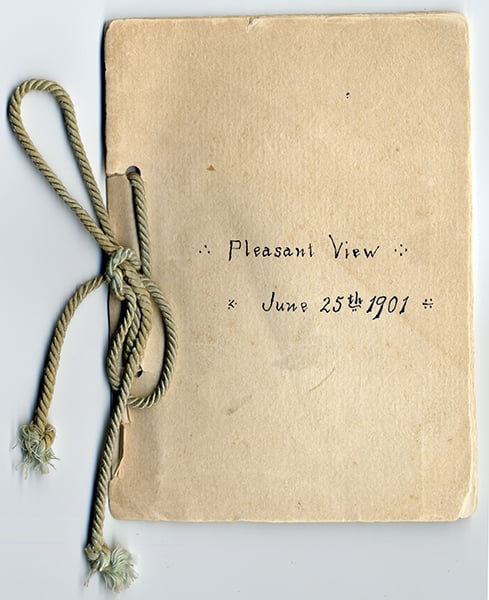

Some of Mr. Kimball’s photographs may have made their way into a hand-crafted souvenir album that is now in the Longyear archives. Although its provenance is unknown, the album was clearly a cherished memento of a special day. And now, almost exactly 115 years later, these images and others offer a window onto that June visit with Mrs. Eddy at her beloved New Hampshire home.

A surprise invitation

Around 1,700 Christian Scientists were already touring Concord on Monday, June 24, when they heard the news: Mrs. Eddy wanted to see them! All plans for departure were quickly canceled, and every possible accommodation was made to ensure that everyone had a place to stay for the night.

“Hotels and boarding houses were overflowed with guests, and many sought the hospitality of private residences, which was cordially given,” reported the Boston Post.1 The residents of Concord were gracious, helpful, and kind in this moment of need.

“Beautiful and friendly homes, never before opened to strangers, were filled to the full with Scientists,” recalled Helen A. Nixon. “Passing pedestrians not only gave information asked, but offered to do more. Cab-men volunteered useful hints. Two gentlemen in discussion on the street corner when asked a question by my friend insisted upon dropping their conversation and supplied our answer by telephoning from a neighboring pharmacy.”2

On Tuesday morning, a trio of special trains carrying ten cars each brought more eager Christian Scientists (and the press) from Boston to Concord. Nearly 1,000 people arrived on the first train, which pulled into the downtown railroad depot shortly after 11:30. From there, the passengers took hacks, wagons, and all other feasible forms of transportation out to Pleasant View.3

“Many rode on street cars as far as the line extended, and walked the remainder of the distance, about a mile,” noted the Boston Post. Others chose to walk the entire two miles from the train station.4

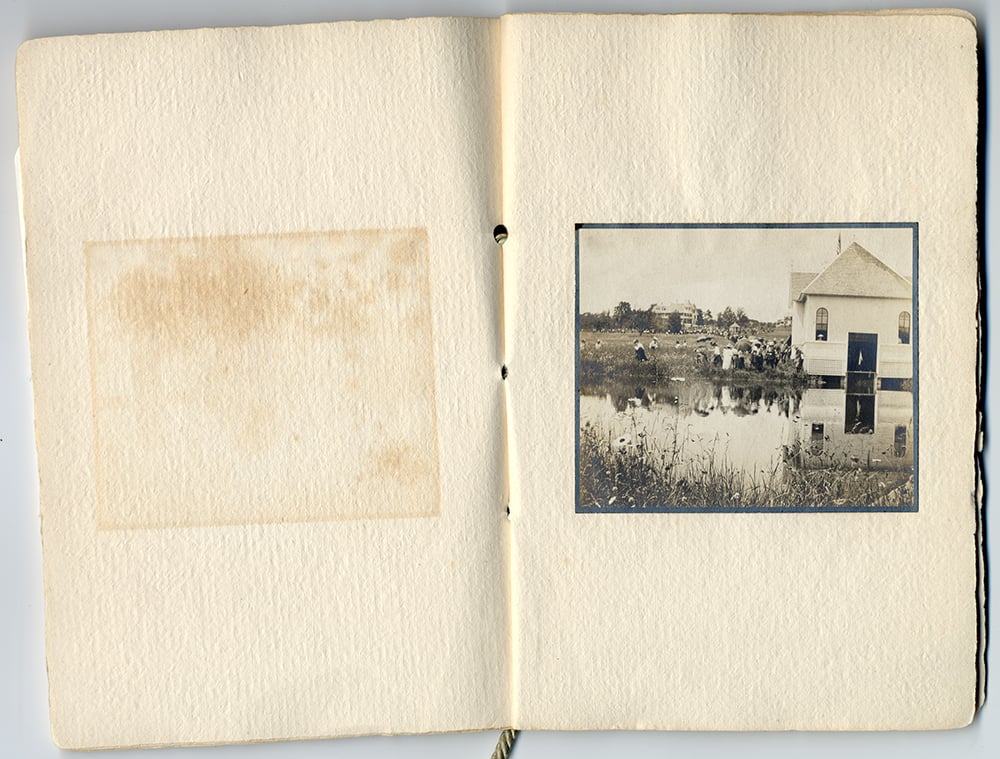

The grounds at Mrs. Eddy’s estate had opened earlier in the day, and were already crowded with visitors. “The tide of people rose … until about noon” as the throng, which ultimately numbered about 3,000, waited patiently “in the blasting heat” for another two hours for Mrs. Eddy’s scheduled appearance.5

Mary Baker Eddy’s greeting

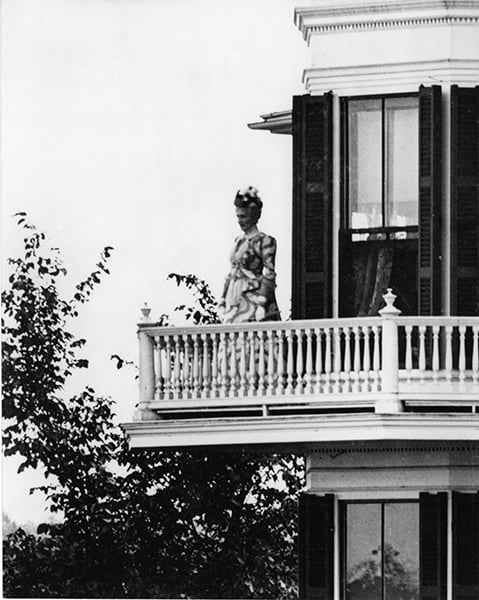

Promptly at 2:00, Mrs. Eddy stepped onto the balcony.

“Her step was firm. Her manner was impressive,” observed a Boston Globe reporter who was present that afternoon. “Her movement was graceful as viewed against the background of sky and the swaying branches of trees, swaying because a slight breeze had risen from the valley that stretched away to the distant hills.”6

The reporter went on to describe Mrs. Eddy’s patterned dress: “She was attired in what might have been satin or silk, figured, and cut en traine. Upon her white hair rested a bonnet, with fluttering blue and old gold trimmings.”

A hush fell over the crowd. Mrs. Eddy’s remarks to her followers were brief, but brimming with warmth: “Beloved brethren: My joy in meeting with you is my present text. When we shall meet again will be my next. I think you all agree with me that you have heard sufficiently from me in my message. I will only look upon your dear faces and then return to my study.”7

The “message” she was referring to, of course, was her Communion message that had been read aloud that Sunday, and which would later be published as “Message to The Mother Church for 1901.”8

Mrs. Eddy appeared “in excellent health and spirits,” the Boston Post reported, clearly “glad of the opportunity to greet her followers.”9 One contributing factor, perhaps, to those excellent spirits? Just three weeks earlier, the court had handed down a verdict in favor of Mrs. Eddy in a lawsuit brought by embittered former student Josephine Woodbury. The suit had dragged on for two long years, and its favorable conclusion must have come as a great relief.

“The most marvelous sense of love”

Mary Eaton, who was standing in the crowd at Pleasant View that afternoon, would later recall that her Leader’s greeting “was full of love, gentleness, childlikeness and humility, and at the same time gave one the feeling that there was a great strength and power in her character and life.”10

For Mary Troxell, a practitioner from Washington, D.C., the visit was transformative. While waiting for Mrs. Eddy to appear, she had felt “the most marvelous sense of love I have ever known — love that satisfies, nourishes, sustains, uplifts, and blesses; love that washes away all that is unlike itself; love that knows only its own purity.” So great was this sense of love, in fact, that Miss Troxell experienced a healing: “All fear for the future, all anxiety and care, dissolved as a dream, a weight of oppression was lifted, and I felt the most absolute assurance of God’s guidance for the future, of His care and enduring, sustaining power and presence.”11

After her brief comments, Mrs. Eddy withdrew from the balcony, reappearing a few minutes later on her front porch, where she prepared to enter her carriage.

According to the Boston Globe, this resulted in “a decorous sort of scamper for the driveway…. That was when a group of girls thoughtlessly and ruthlessly rushed across a bed of flowers in order to reach a place close to the pillars of the porte cochere.”12 John Salchow, Pleasant View’s handyman and head groundsman, reminded them “they were destroying things that Mrs. Eddy loved” — which quickly resolved the situation.13

Mrs. Eddy entered her carriage. The door was shut. “The footman climbed upon the seat with the coachman, both wearing high silk hats. The whip was cracked and off galloped the pair of splendid horses….”14

After the carriage’s departure, the crowd was free to partake of the beauty of Pleasant View.

“They enjoyed themselves very much, for the grounds are charming,” enthused the New York Journal. “There were many very young men and women among the visitors, who gathered flowers by the brink of the lake.”15

Mrs. Eddy’s next invitation to Pleasant View wouldn’t come until the summer of 1903 — at which time some 10,000 people showed up, making headlines nationwide. Ever alert to the dangers of personality and popularity, in the spring of 1906 Mary Baker Eddy would communicate the following through the Christian Science periodicals: “Divine Love bids me say: Assemble not at the residence of your Pastor Emeritus at or about the time of our annual meeting and communion service, for the divine and not the human should engage our attention at this sacred season of prayer and praise.”16 In 1908, she would abolish the Communion service at The Mother Church altogether. On this beautiful June afternoon in 1901, however, those changes were still in the future, and this would be a day fondly remembered both by the citizenry of Concord17 and by the Christian Scientists who experienced it.

Several of her students wrote to Mrs. Eddy afterwards, thanking her for her hospitality and inspiration, including Victoria H. Sargent, a practitioner and teacher from Wisconsin:

It was so kind of you to let us come to your dear home and see you and hear your sweet strong voice…. May Infinite Love help each one of us to share our appreciation for all you have done for us in working for our blessed cause.18

A message that bore fruit

Ultimately, it wasn’t just Mrs. Eddy’s personal appearance and warm greeting that resonated with her followers. The Communion message she had given them also bore fruit.

For Mary Troxell, Mrs. Eddy’s greeting that afternoon “turned me anew to her grand Message, and I have spent many hours with it since, always finding strength and help. When I left Pleasant View, I said in my heart, ‘Lord, it is good for me to have been here,’ and I pondered deeply the hallowing influences of that wonderful day, and the marvelous power for good in a single human life, directed and sustained by God.”19

Likewise Mary D. Rice, a practitioner from Denver, Colorado, would recall that when Mrs. Eddy said to the gathered throng “‘I think you will all agree with me that you have heard sufficient from me in my message,’ little did I then realize what this ‘Message’ meant to me and my work. After returning home, and making this a daily study, it gradually unfolded to me.” Miss Rice went on to recount how, thanks to the inspiration gleaned from that Communion message, she helped bring about a beautiful healing of a man addicted to alcohol and gambling.

“He has been satisfied with his home and family ever since,” she records. “When I think of what we have received through this message … I can say with all my heart, ‘Blessed be the Lord, who, through his chosen messenger, daily loadeth us with benefits.’”20