“Science is absolute and final. It is revolutionary in its very nature; for it upsets all that is not upright,” Mary Baker Eddy told a national gathering of Christian Scientists in Chicago just a few weeks before July 4, 1888. “Christian Science and the senses are at war. It is a revolutionary struggle. We already have had two in this nation; and they began and ended in a contest for the true idea, for human liberty and rights. Now cometh a third struggle; for the freedom of health, holiness, and the attainment of heaven.”1

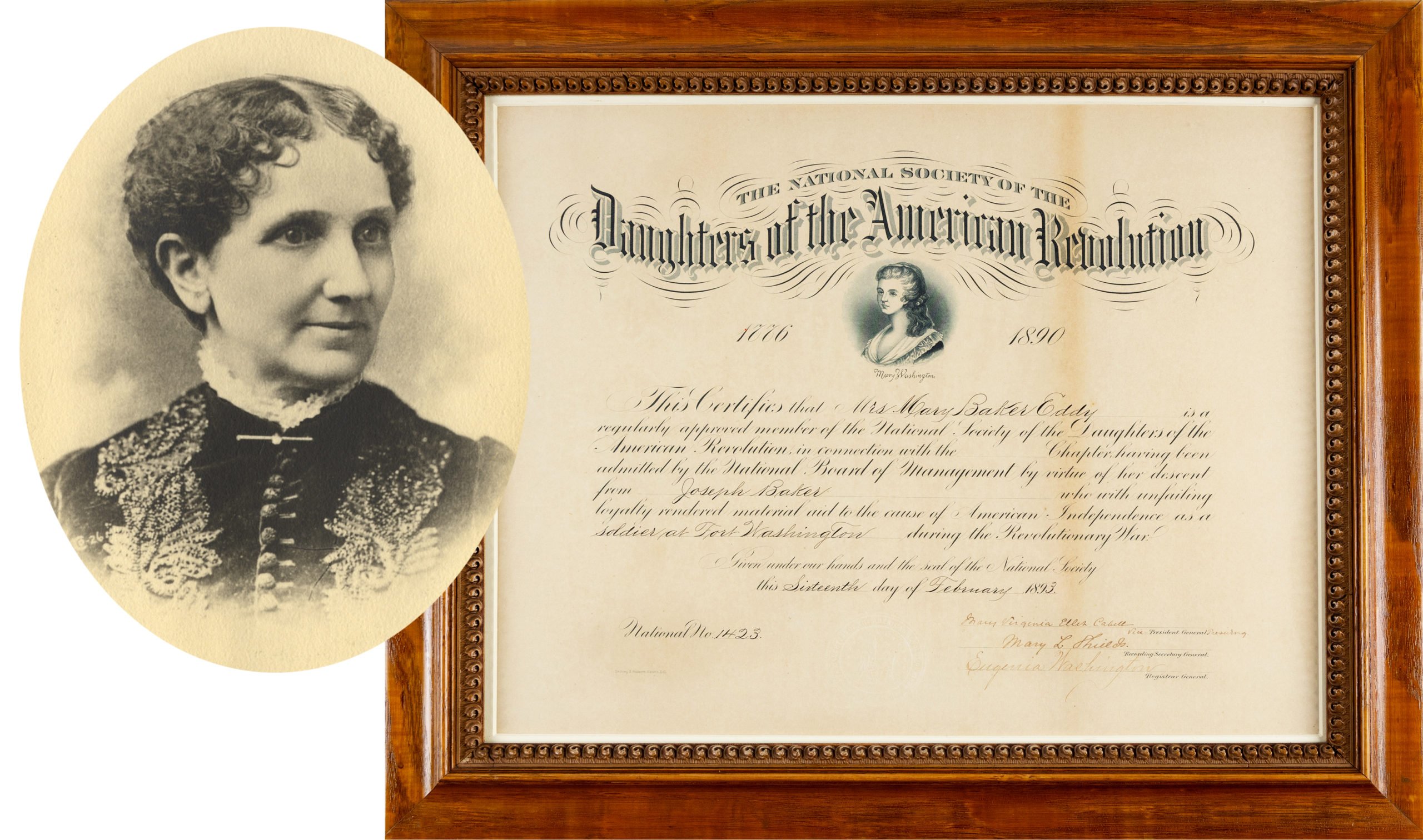

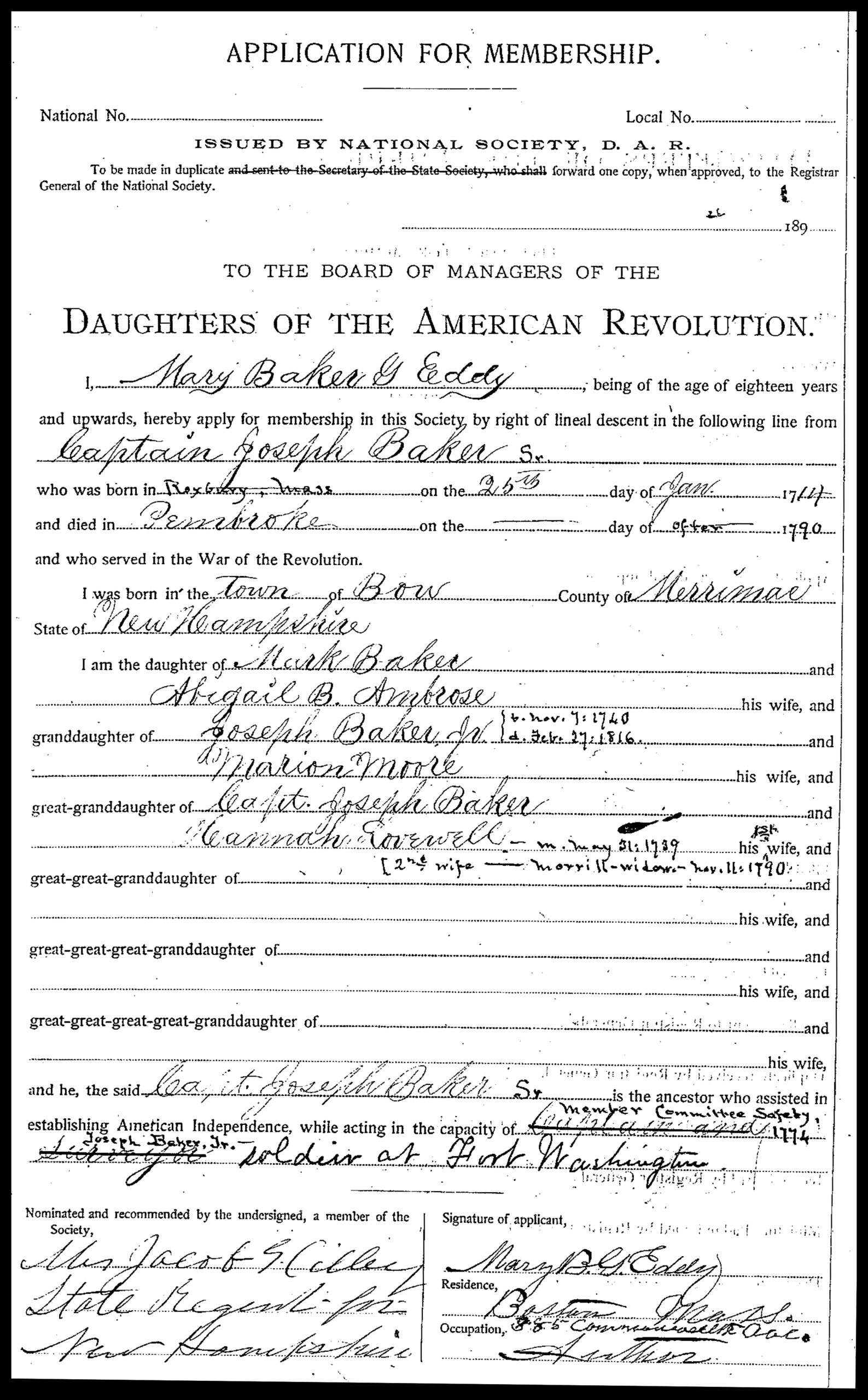

As the Leader of this “third struggle” for freedom, Mrs. Eddy had a keen appreciation for those who fought for her country’s independence and ideals. Within a few years of the 1890 founding of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Mrs. Eddy’s friend Martha Cilley urged her to join the patriotic group. Mrs. Cilley, the daughter of one of Mrs. Eddy’s childhood ministers, was the DAR’s state regent for New Hampshire.2

Mrs. Eddy did apply, naming as her patriot ancestor her paternal great-grandfather Joseph Baker. She did not know the details of his role in the Revolutionary War, but she wrote that he had been commissioned as a captain and had surveyed land in New Hampshire. What later became clear was that Joseph Baker had become a captain years before the Revolution, but both he and her grandfather of the same name had served the cause, qualifying her for the DAR.3

Capt. Joseph Baker

Born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Joseph Baker, Mrs. Eddy’s great-grandfather, married Hannah Lovewell in 1739. The couple built a homestead on land that Hannah had inherited in what would later become known as Pembroke, New Hampshire.4

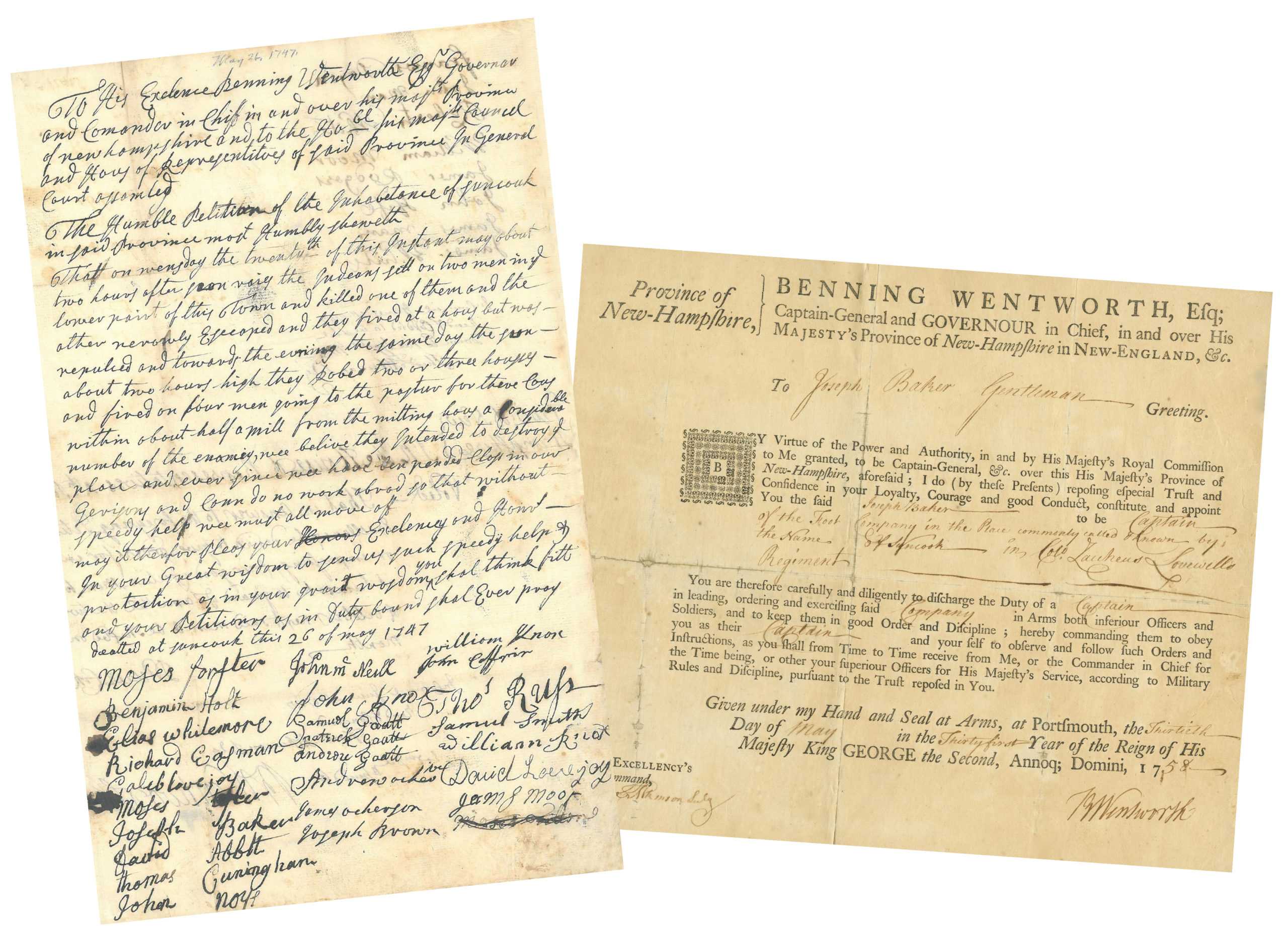

In 1747, Joseph Baker joined other Pembroke settlers in signing a petition requesting that the colonial governor of New Hampshire provide protection for the new settlement after several raids by Native Americans.5 In 1758, he joined other New Hampshire men in the Crown Point expedition (on what would later become the border between New York and Vermont) as part of the French and Indian War.6

As tensions brewed over British rule, the people of New Hampshire grew tired of appealing to London, and the desire for self-government grew. But some remained loyal to the British, so in 1774, in response to a call from the American Continental Congress, Pembroke voters elected Captain Baker to a Safety Committee, “to Carefully observe and Look to the Behavier [sic] of all Persons within their Limits” and to publish the names of any found to be disloyal to the Revolutionary cause.7

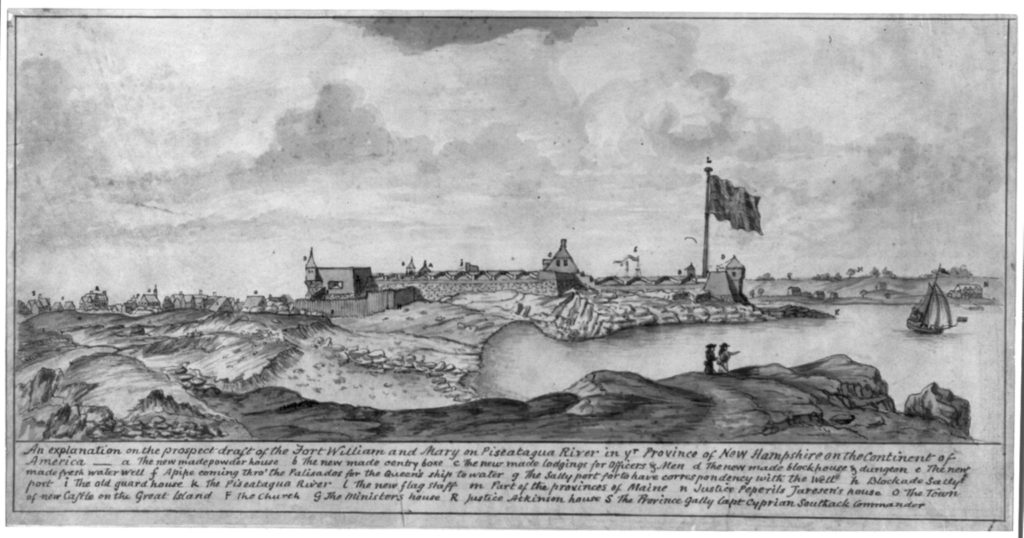

That same year, rebels drove the British away from Fort William and Mary in Piscataqua Harbor at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, lowering the fort’s British flag and taking gunpowder and other supplies.8

The following spring, on April 19, 1775, the battles of Lexington and Concord sparked outright war. As men from both Massachusetts and New Hampshire rushed in droves to help defend against the British (see article about Gen. Benjamin Pierce and the Baker family here), New Hampshire delegates gathered two days later at the Third Provincial Congress in Exeter to respond to the events. They voted unanimously to name a leader for the men who had gone to fight. It was a timely decision, as the Committee received a letter from Massachusetts on April 23 indicating that about 2,000 men from New Hampshire had come bravely to assist, but needed field officers.9

As of April 25, Captain Baker represented the town of Pembroke at the Third Provincial Congress.10 The next day, the representatives voted that each town would store its share of biscuit flour and pork for emergency use and would “Engage as many men . . . as they think fit to be properly Equipt & ready to march at a minute’s warning on any Emergency.”11

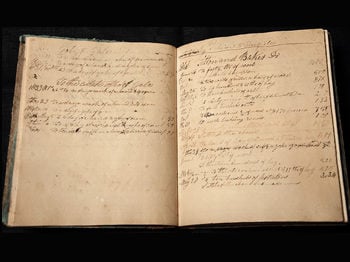

A year later, the New Hampshire government required white males above age 21 to sign a loyalty oath, or “Association Test.” It was a precursor of sorts to the national Declaration of Independence, which would come that July. The signers of the oath in New Hampshire, who included Captain Baker, promised: “WE WILL, TO THE UTMOST OF OUR POWER, AT THE RISQUE OF OUR LIVES AND FORTUNES, WITH ARMS, OPPOSE THE HOSTILE PROCEEDINGS OF THE BRITISH FLEETS AND ARMIES AGAINST THE UNITED AMERICAN COLONIES.”12 They stood ready to be called into battle at any time.

Two grandfathers, two patriots

Captain Baker’s son and namesake Joseph Baker married in 1762, when he was about 22, and moved across the river from Pembroke to Bow, New Hampshire. There he built the farmhouse where he and his wife, Maryann McNeil Moore Baker, would raise their children, including Mark, born in 1785. Mark would inherit the house and raise his family there, too. He and his wife, Abigail Ambrose Baker, had six children, the youngest of whom was Mary.13

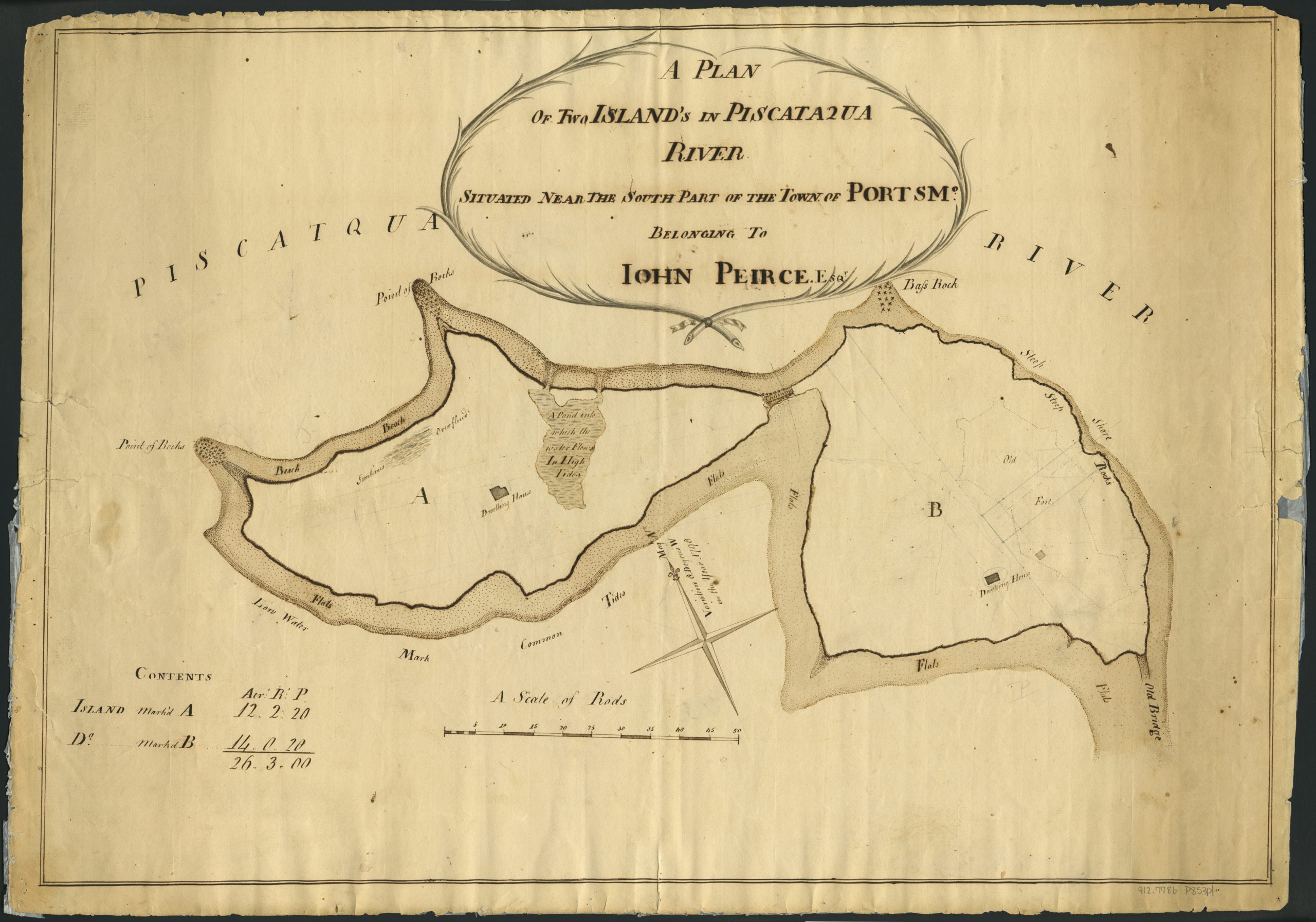

As his father did in Pembroke, the younger Mr. Baker signed the Association Test when it circulated around Bow in 1776.14 A few years later, in 1779, he would serve as a “matross man,” a coastal artilleryman, at Fort Washington in Piscataqua Harbor.15

That earth and stone fort was built in 1775 on Peirce Island, one of three small forts designed to keep the British from getting through the narrows of the Piscataqua River near Portsmouth. The matrosses were prepared to shoot at any enemy vessels. In October 1775, they managed to capture a British ship that accidentally headed toward Portsmouth instead of Boston, intercepting nearly 2,000 barrels of flour intended for British troops. The flour not only fortified Portsmouth soldiers, but a large portion also made it to George Washington’s troops in Boston.16

Nathaniel Ambrose, Mary Baker Eddy’s grandfather on her mother’s side, also signed the Association Test in Pembroke and served as a soldier during the Revolutionary War. He was captain of the Sixth Company of Col. Joseph Badger’s regiment of militia men in 1776 and marched to New York later that year under Col. Daniel Moor.17

In 1777, Captain Ambrose helped defend a garrison at Ticonderoga, under Lt. Col. Ebenezer Smith.18 He earned a little over three pounds for that mission. But he earned five times that amount in the fall, when his company of volunteers joined the Continental Army under Gen. Horatio Gates in Saratoga, New York. British Gen. John Burgoyne surrendered in Saratoga in October, a turning point that protected New England from being cut off from the rest of the colonies.19

“A child of the Republic, a Daughter of the Revolution”

On Sept. 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the Revolutionary War. Less than 100 years later, the U.S. endured the severities of the Civil War to prevent a split in the union. In 1865, that war drew to a close, and the ratification of the 13th Amendment officially ended slavery.

The very next year, in 1866, Mrs. Eddy (then Mrs. Patterson) found healing and a new sense of Life as God with her discovery of Christian Science.

By the time she joined the DAR in 1892, she had founded the Church of Christ (Scientist) in Boston, but had moved back to Concord, New Hampshire a few years earlier.20

“I have one innate joy, and love to breathe it to the breeze as God’s courtesy,” she later commented in honor of New Hampshire’s “Fast Day,” which was renamed “Patriot’s Day” in Massachusetts to commemorate the Revolutionary War. “A native of New Hampshire, a child of the Republic, a Daughter of the Revolution, I thank God that He has emblazoned on the escutcheon of this State, engraven on her granite rocks, and lifted to her giant hills the ensign of religious liberty — ‘Freedom to worship God.’”21

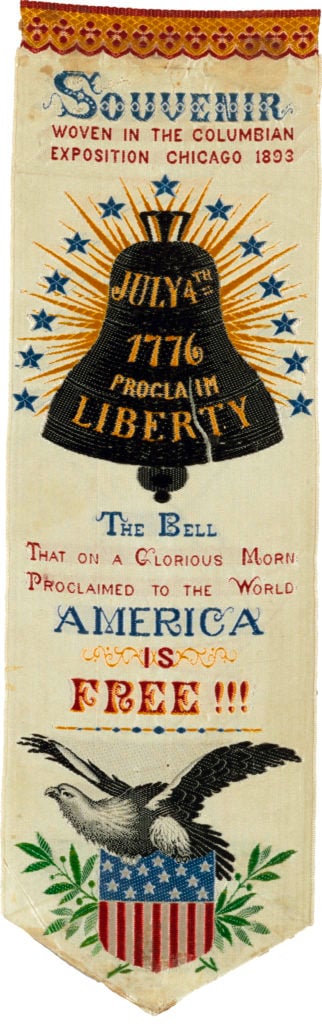

In 1893, when a DAR committee wanted to cast a bell for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and tour it around to sites significant to United States history, Mrs. Eddy supported the idea. She asked The Christian Science Journal to print the committee’s letter, announcing: “It shall ring at sunrise and sunset; at nine o’clock in the morning on the anniversaries of the days on which great events have occurred marking the world’s progress toward liberty; at twelve o’clock on the birthdays of the ‘creators of liberty;’ and at four o’clock it will toll on the anniversaries of their death.”22

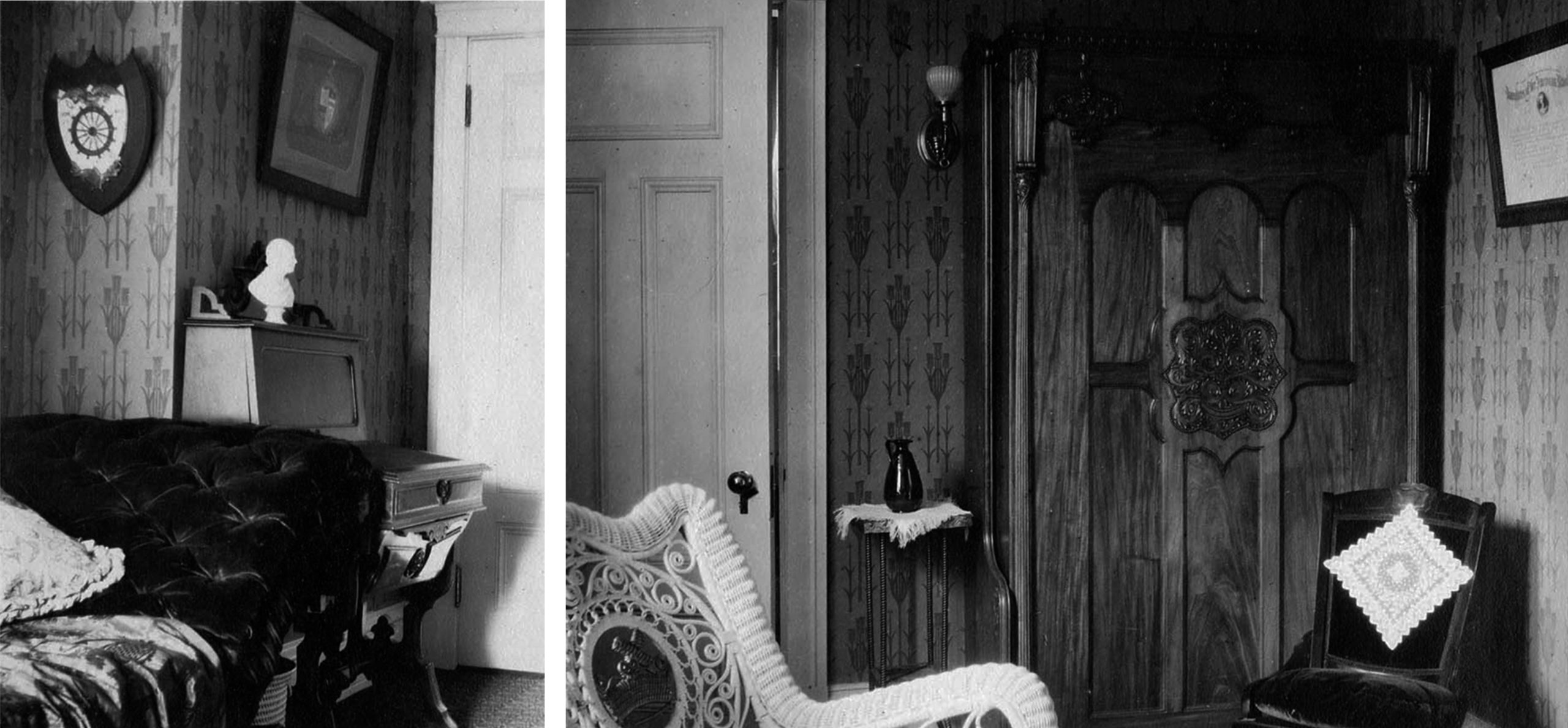

Mrs. Eddy contributed to the fund and displayed a small replica of the bell at her Pleasant View home in Concord, and, later, at 400 Beacon Street, her home in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. She also put up her framed membership certificate and a plaque from the DAR.23

During the final class she taught in 1898, Mrs. Eddy wore a beautifully jeweled DAR pin given to her a few years earlier by Effie Andrews, a Christian Scientist from New York who attended the class.24 “Few things earthly could give me more pleasure than the insignia of the ‘Daughters’ which you named,” Mrs. Eddy had written when Mrs. Andrews, a fellow member of the society, offered to send her the pin engraved with Mrs. Eddy’s membership number. The letter continued, “I have longed to meet with them [the DAR]. But I have so much to attend to that none else but I can do. I have to sacrifice all these worldly pleasures.”25

On Independence Day in 1902, Mrs. Eddy sat in her swing on the upper veranda at Pleasant View and spoke to her student Anna B. White Baker about freedom according to Christian Science. “Thinking of our flag, this comes to me,” she said, “that the motto emblazoned on the escutcheon of Christian Science is, ‘Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free,’ free from the domination of evil. We are governed by God, He is our only governor. We are not governed by evil. Now in this lies your freedom.

“The independence of the Christian Scientist can be won only by turning away from seeking independence in mortal mind, for matter is but the substratum of mortal mind,” she continued. “My forefathers landed on Plymouth Rock in search of religious liberty, and I have steered the ship of Christian Science, standing at the helm and at the rudder and doing most of the work, and I have landed on the Rock of Truth. We must fight for our freedom. It will not do to sit down and dream or sleep, and expect to win, but we must fight and strive. We must strive, for Jesus said, ‘I say unto you, “Strive to enter in at the strait gate.”’”26