Tracing Boston’s progress during the early days of Christian Science is interesting and worthwhile. The years from 1880 to 1910 were a time of great growth for the Cause of Christian Science. During this time the church evolved into a worldwide movement, with Mary Baker Eddy fulfilling her role as Founder and Leader. Boston, too, experienced enormous growth during the period. This article provides a brief look at several aspects of the city during that era, with the hope of presenting broad impressions of the atmosphere in which Christian Science was nurtured and perhaps giving a better understanding of the city which Mrs. Eddy chose to be the headquarters of the Christian Science movement.

Innovation and Invention

1880 to 1910 was a time of renewal for Boston. In 1880, the city was still recovering from the fire of 1872 and, along with the rest of the nation, from the financial panic of 1873. A brilliant new era was ahead, however gloomy it may have appeared to poor and wealthy residents alike. Popular topics of debate in those years included civil and social reform, labor disputes and women’s rights. Hopes filtered to the general populace that Utopia was an imminent possibility. Individual action often seemed inspired by Biblical teachings and sincere religious fervor. An assortment of enterprising developments ensued, a sampling of which follows:

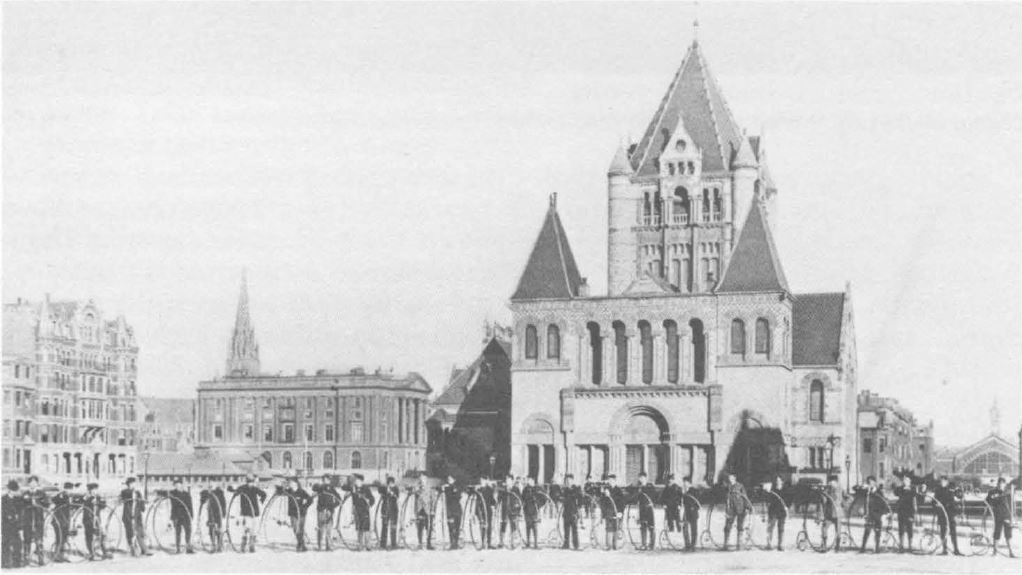

Architecture: The Boston Public Library (McKim, Mead & White, 1895) built across Copley Square from Trinity Church (H. H. Richardson, 1877); the two are representative of the finest in American architecture of the period.

Aviation: Longest flight over salt water in the United States, 1910 — round trip from Quincy to Boston, 33 miles; part of the largest and most important aviation meet held in the U.S. up to that time.1

City Planning: First metropolitan park system established and planned about 1893; extensive parkland in advance of urbanization, with landscape architecture by Frederick Law Olmsted.

Education: New concepts of kindergartens, playgrounds and cooking classes added to public schools; world’s first kindergarten for blind children.2

Engineering: Largest lock gates in America in 1908, built at Charles River basin — first of the electric “sliding gate” type, later used for Panama Canal.3

Invention: Disposable safety razor blade developed and marketed in Boston, 1905 (King C. Gillette); idea of level measurements for recipes (Fannie Farmer).

Journalism: Numerous one-man newspapers, including reform magazines such as New England Magazine, edited by Edward Everett Hale, and Woman’s Journal, organ of the American Woman’s Suffrage Association, edited by Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of Lucy Stone. In 1886 there were 300 newspapers and magazines published regularly in Boston. Mary Baker Eddy founded The Christian Science Monitor in 1908, which contrasted sharply with the yellow journalism of most major newspapers.

Music: Boston Symphony Orchestra founded in 1881; “Pops” Concerts begun in 1885.

Religion: Mary Baker Eddy became the first American woman to found a church. Some major changes within traditional religion originated in Boston, such as the Reform movement of Judaism in the 1880s, and the Emmanuel healing movement within the Episcopal Church.

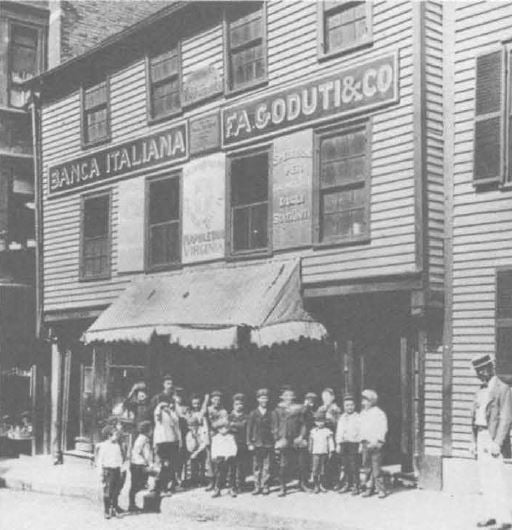

Social Services: Robert Woods adapted settlement house idea to Boston’s needs. Others made first American efforts to protect Italian immigrants from exploitation of padrone system. Simmons College, world’s first full-time school of social work.

Transportation: First underground subway in America (1898); first underwater subway tunnel in North America (1904); first American-made bicycles.

In an article entitled “My Recollections of Boston — The City of Kind Hearts,” Helen Keller wrote, “It has ever been in Boston’s creed to render life safer and happier for the coming generation.”4 Bostonians were quick to adopt modern inventions for making life easier, from the bicycle to the telephone, which had been invented in Boston in 1876. The first electric lights in Boston were installed at the luxurious Hotel Vendome on Commonwealth Avenue in 1882, and in lecture halls. Later in the 1880s, “…on Boston Common, a single arc light with its energizing engine and dynamo was set up…as a curiosity for the public to see. The tents of Barnum’s Circus were lighted by electricity as an unprecedented spectacle at that era.”5 The Mother Church acquired the city’s first electric action organ in 1895.6 And of course the church was illuminated with the new electric lights.

Life in Boston

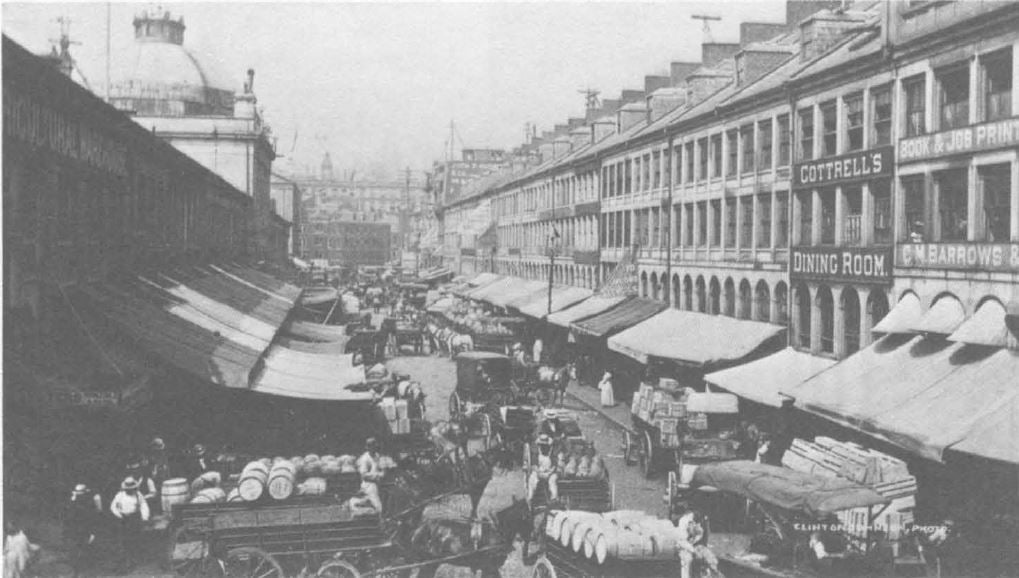

Life for most Bostonians was still rather provincial in the 1880s. Some of the city sounds were described as follows: “…the great and the universal noise in the city was the pounding pavements. That sound began before dawn when the milk carts came by thousands into the city from the outlying farms. By nine o’clock the tens of thousands of horses, including those that drew the cars of the horse railways, the carriages of the physicians and merchants, the tip carts of the street cleaners and the long drays of the sugar refiners and the wool merchants, were on the move. The horses of the street railways dangled bells from their collars. Dray horses had bells. Therefore much bell music was mingled with the pounding street noise…. At sunset the noise abated, but through the early night the pounding and the sound of iron tires rolling on stone and gravel went on.”7

The street railway was Boston’s line of horse-drawn cars pulled along tracks. During rush hours cars were filled to capacity — about 40, including standees. These heavier cars required four to six horses to draw them. For warmth in the unheated horse cars, aisles were heaped with straw. Children loved to revel in it, sometimes finding coins dropped by other passengers.

Boston was still a walking city in the 1880s. Getting to work on foot was a necessity for low-income people who could not afford carfare. Hundreds of employees trekked daily across the Channel Bridge, bound for industries in the South End, among them foundries and piano factories.

Around 1885, the safety bicycle was introduced from England, and the air tire soon followed, replacing the wooden velocipede and the faster but precarious Columbia high-wheeler. One bicycle manufacturer advertised its product as “AN EVER SADDLED HORSE WHICH EATS NOTHING.” People by the tens of thousands rode their bicycles in and around Boston. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison recalled that, “From dusk to about 10 P.M. the street was filled with young people learning to ride the bicycle, and resounded with tinklings, crashes, squeals and giggles.”8

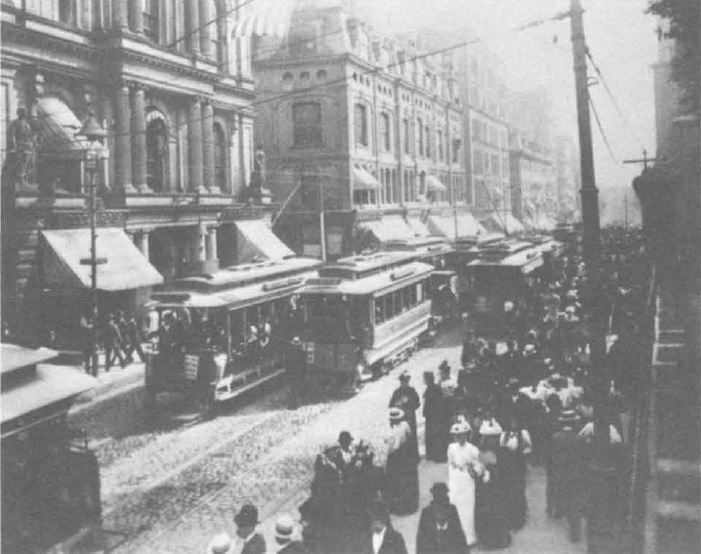

After 1885, the roar of electric street railway cars mingled with the rest of the noise. These gradually replaced the horse cars by 1900. The electric cars acquired the local nickname of “broomstick cars” because of the trolley poles connecting them with the wires overhead. By 1910, trolley lines reached even the smallest towns in Massachusetts.

In heaviest traffic and on narrower streets, the speed of the all-electrified street railways was quite reduced. Going underground became a necessity, so Boston became the first American city to build a subway for trolley cars, completed in 1898, under Boston Common.

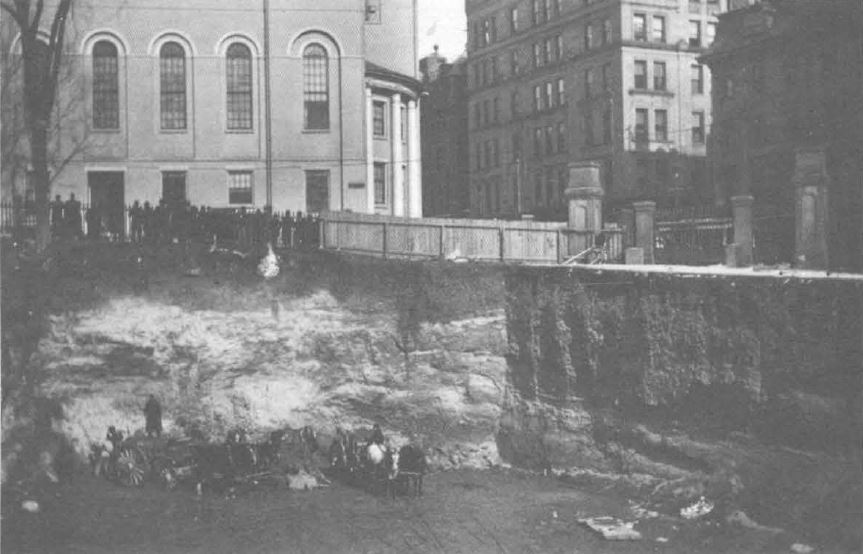

The Back Bay landfill project, begun in the 1850s, was nearly complete by the late 1880s. Fill was brought in from the outlying town of Needham to build up the tidal area west of the Public Garden and provide much needed expansion room for the city. The Mother Church was erected in the new Back Bay area in 1894. Mrs. Abbie W. Griffin recalled an interesting story about the land on which the church was built. She wrote, “Years ago ‘Back Bay’ extended its waters from the Albany R.R. Huntington Ave. over what is now ‘the Fens’ excepting ‘Gravelly Point,’ an island three cornered in shape, which was the only solid ground in that region. The present Back Bay district excepting that point is made land (filled in). Mr. Griffin who was an expert Conveyancer, was employed over a year in examining the titles of that territory for the City of Boston. He discovered and told me that the lot selected and presented by Mrs. Eddy for The Mother Church was this same ‘Gravelly Point.’ …The Directors were glad to know this when I told them…. The building of the church proved the above to be correct, hence the three cornered church on solid ground.”9

Frederick Law Olmsted, America’s first landscape architect (and designer of New York City’s Central Park and many other major park systems in the United States), ingeniously transformed the marshy, malodorous Back Bay Fens into a beautiful park area by 1885. This later linked other segments of parklands with tree-lined strands to form an “Emerald Necklace” of typical Olmsted “manufactured wildness,” some five miles in length. The South End, which had connected Boston with the mainland before the landfill project, became the nation’s largest rooming house district.

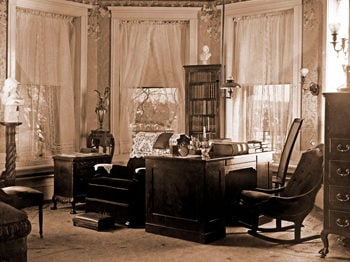

The South End neighborhood is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places as the best example, and the largest, of Victorian planning in the country. In 1882 Mary Baker Eddy leased 569 Columbus Avenue, a four-story brownstone in this district, in which she established the Massachusetts Metaphysical College. The following year this was the first address of the Christian Science Publishing Society. In 1884 the college moved to the slightly larger house next door at 571 Columbus Avenue.

Challenge of Immigration

Because of its significance for our society today, late Victorian Boston is studied closely by historians, political economists and sociologists. The original Puritan and Yankee character of Boston had greatly disappeared by 1880. The socially and culturally elite Boston Brahmins and literary giants of the earlier 19th century had faded from the scene. Almost two-thirds of the population consisted of the foreign-born and their offspring. The proud and sometimes complacent “Hub of the the Universe” (as Boston was called) would never be the same. Like many American cities forced at that period to stretch at the seams, Boston had its share of problems, and its share of reformers to deal with the problems.

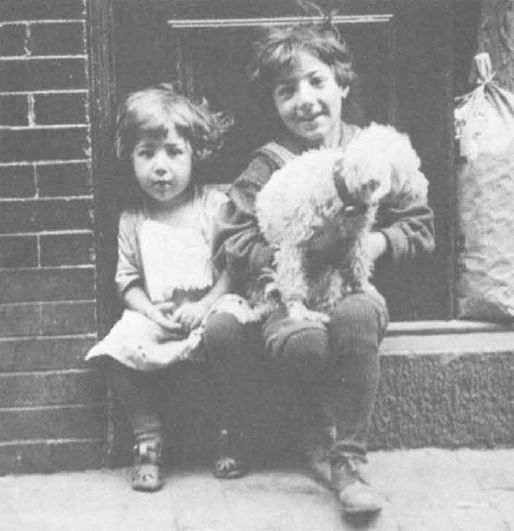

Newest arrivals to Boston usually stopped first near their embarkation point, — the waterfront slums, with the lowest rents, lowest elevation, and poorest drainage in the city, and the highest population density after Calcutta. Problems resulting from the overcrowding involved sanitation, employment practices, imbalance of the sexes, and destitution of those who couldn’t cope with the shock of being transplanted. In their letters to the Old Country, some immigrants discouraged others from coming to Boston, so ill-prepared was the city to receive them. Some stayed only until enough funds could be saved to return home.

Cameo scenes of immigrant neighborhoods were described by two social workers: “The street offers much to vary what is otherwise often a life of monotony and toil. The street piano, which is an ever-present, ever-welcome entertainer, starts the children dancing.” “…pushcarts loaded with fruit and vegetables, fish and crabs, and edibles of every description preempted the sidewalk, the gutters, and most of the street. Cries of ‘Hot tamales,’ ‘Fresh bagel,’ and ‘Fish! Fresh fish’ in Yiddish, Italian and Portuguese filled the air.”10 An older resident recalled overhearing three boys wrangling together. One was Jewish, one Irish, and the other black. They were communicating — in Yiddish!

In 1900, immigrants outnumbered Bostonians of colonial descent three to one. The many effects on society were met with a positive response by some “Beacon Hillers,” but some wealthier people just ignored the problems, and still others complained — or endeavored as early as 1884 to hold back the tides of immigration. The Immigration Restriction League worked in the 1890s to require literacy tests for naturalization. Social workers were hard-pressed to handle the influx of newcomers. It was obvious that old charitable methods were helpless in Boston’s situation and that new methods were needed.

Social Reform

Genuine and widespread concern for the unfortunate developed during the 1880-1910 era. In Boston, Julia Ward Howe (author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”) and abolitionist Wendell Phillips fostered these concerns about as much as anyone. The two were from the city’s First Families, yet both rebuked elite society as well as the educated of all classes who disregarded their fellow men in need.

The means of scientifically studying social conditions and interrelationships was developed in the 1880s and ’90s. “Social reconstructionism” became a profession, and workers tried to merge ethical motives with scientific methods in order to improve American life.

An important educational vehicle for many students of social reform was the university settlement house. The first such center, providing community services such as gymnasiums, baths, classes, reading rooms, and relief work in underprivileged areas, was started in London in 1875. Jane Addams adapted the concept in Chicago at Hull House. In 1891, Robert Woods opened Andover House, later renamed South End House, in Boston’s South End section.

America’s pioneer sociologist, Robert A. Woods came from Pittsburg and trained for the ministry at Amherst and Andover. While seeking to serve mankind in the best way possible, he sought spiritual guidance and recorded in his diary at the time, “God is striving to realize some great thought in the history of mankind. We can know that thought only by working together with God.”11

It occurred to Woods that special expertise must be gained to meet the challenges caused by the recent waves of immigration. The settlement house idea appealed to him as the best way for Christianity and democracy to join in dealing with social problems. He wrote, “The settlement is an intellectual and moral adventure having its origin in the university and the church….its chief discovery or rediscovery is the neighborhood as the vehicle of secular good will and as the unit of civic and national reconstruction.”12

Woods was determined to avoid the appearance of imposing on an impoverished people his own ideas of what was needed, as had some previous well-meaning charitable efforts. Staff members (usually university faculty and students) were required to reside among the people being served, hence the term “university settlement.” Only in being part of the mixed-immigrant neighborhood could they honestly expect to serve it with wisdom and empathy. His efforts were evidently quite successful, for a dean of the Episcopal Theological School wrote of Robert Woods in 1901, “He is today one of the strongest influences for good in the city of Boston.”13

Settlement houses were founded in Boston by various colleges and churches, as well as one with a temperance connection. Several settlement houses branched out from South End House, aiming to serve the needs of black and Italian neighborhoods. The groundwork done in all these settlement houses also had national implications. The present-day field of sociology derived from published studies of the unique philanthropic agency of the settlement house, as developed in Boston.

There is a tendency on the part of some scholars today to belittle the early work, — to imply that Woods was naive in his attempt to impose middle-class morality and Yankee values on Boston’s ethnic subcultures. And yet the work at South End House remains an outstanding example of what one person’s vision can do to help the unfortunate. The accomplishments of the settlement houses during this period, — helping to uplift and reclaim impoverished neighborhoods — were carried out without one dollar of government funding, even during periods of economic depression.

In some ways, Boston was a schoolroom for the nation, — providing lessons for many new Americans who later settled elsewhere in the country; and with textbook material for coming generations of analysts of the period. All who passed through were touched by Boston in some way. It is to be hoped that what they gained helped them to become absorbed in the American way of life, enabling them to contribute to the nation-building, and drawing ever more newcomers by their example.