Downy Woodpecker. Scarlet Tanager. Long-billed Marsh Wren. What do these birds have in common? Along with dozens of their feathered kin, they all made it onto a list of bird species spotted at Mary Baker Eddy’s Chestnut Hill home in 1909.

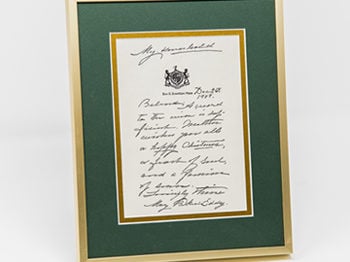

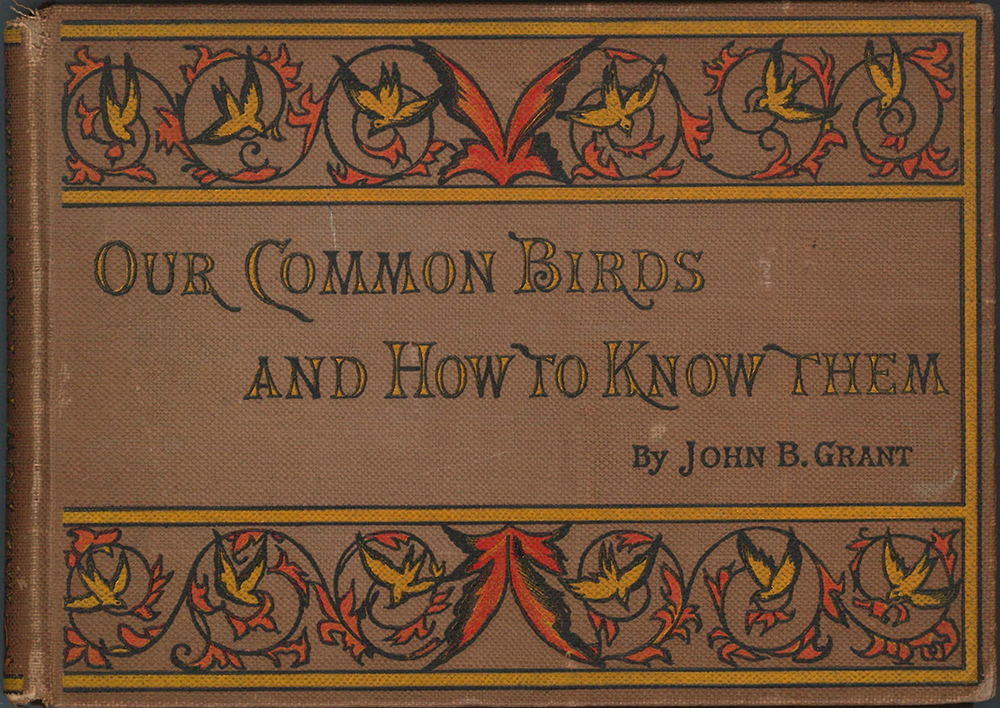

Discovered tucked inside William R. Rathvon’s copy of Our Common Birds and How to Know Them by John Beveridge Grant,1 this typewritten list not only offers a glimpse into Mr. Rathvon’s own personal interests, but also into daily life at 400 Beacon Street, where he lived from November 1908 until the time of Mrs. Eddy’s passing in December 1910.

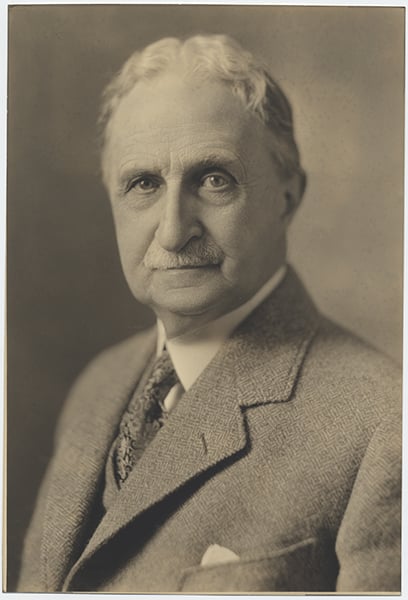

Born and raised in Lancaster, Pennsylvania,2 William Rathvon went West as a young man. He eventually ended up in Colorado, where he became a successful businessman, with most of his wealth in silver mines. Wiped out financially in the “Panic of 1893,” he found Christian Science while visiting Chicago, and it was there that he and his wife Ella took primary class instruction from Mary W. Adams, a student of Mrs. Eddy’s. Afterwards, the Rathvons returned to Colorado, where they did pioneering work in Christian Science. Mr. Rathvon also continued his business endeavors for a time, and became successful in the oil industry.

The Rathvons’ education in Christian Science continued in 1903, when they were invited to attend a Primary class taught in Boston by Edward Kimball under the auspices of the Christian Science Board of Education,3 and then in December 1907, Mr. Rathvon was invited to go through Normal class with Judge Septimus J. Hanna.4

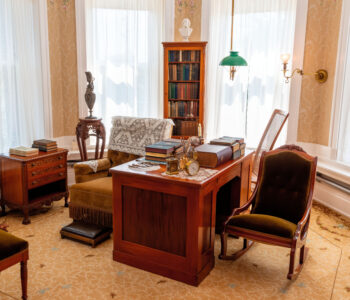

Returning again to Colorado, Rathvon was called back to Boston in November 1908. This time, however, he went to the village of Chestnut Hill, to serve as corresponding secretary at Mrs. Eddy’s home on 400 Beacon Street. Mrs. Eddy received copious amounts of mail and telegrams from well-wishers in the field, including those asking for healing, reporters seeking interviews, and the like, all of which needed to be dealt with. While she had multiple secretaries lending a hand, her correspondence was Rathvon’s primary responsibility.5

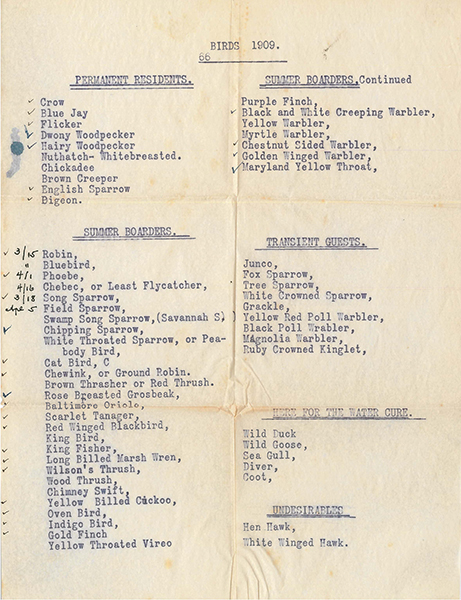

Rathvon may have become interested in birds well before living in Chestnut Hill. His copy of Our Common Birds and How to Know Them was published in 1891, and bears a stamp on the inside cover with the date May 15, 1897. The slim volume includes tips on where and when to go birding, an example of a bird-watching journal, 64 black-and-white photographs, and a short section on the scientific aspects of ornithology. The typewritten list found folded inside has checkmarks and a few handwritten dates beside each bird that Mr. Rathvon spotted.

Given the scope of his responsibilities, it’s unlikely that Rathvon had much opportunity for bird-watching, but of the 60 birds on the typewritten list, he managed to check off 31 that year, including such “Permanent Residents” as Blue Jays, Flickers, and English Sparrows, along with a host of “Summer Boarders,” from Robins and Bluebirds to Goldfinches and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks.

Rathvon may not have been the only birding enthusiast in Mrs. Eddy’s household—one worker kept a pocket diary listing 90 different species of birds in 1910.6 And while the staff needed to be prepared at any time to respond to a call from the Leader of the Christian Science movement, there were moments of leisure, particularly in the early morning before Mrs. Eddy entered her study, and in the afternoon when she went on her daily carriage rides. Her staff lived “normal and happy” lives, according to one member of her household,7 enjoying the occasional bicycle ride (all of the secretaries owned bicycles), as well as such hobbies as amateur photography and astronomy.8

The Chestnut Hill neighborhood has transformed since Rathvon was recording birds in 1909, and some of the species listed have probably left never to return, but Mrs. Eddy’s home at 400 Beacon Street, which is situated on eight wooded acres,9 is still a haven for many feathered visitors. In the month of June 2015 alone, a Longyear staffer saw wild turkeys fly up to roost in trees in the front yard, witnessed a young hawk perched at eye level outside Mrs. Eddy’s study, and spotted many smaller birds that could have used William Rathvon’s help—or that of his copy of Our Common Birds—in identifying.