Longyear Museum’s purpose is to keep Mary Baker Eddy’s history before the public. One of the many avenues used to fulfill this purpose is Quarterly News (now known as the Report to Members).

It was in the Spring of 1964 that Quarterly News made its first appearance. As a research oriented publication, it presents topics relating to Mary Baker Eddy and the formative years of the Christian Science movement. Articles over the past thirty years have provided information about individuals associated with Mary Baker Eddy, places of historic interest, and the Museum’s collection of manuscripts, letters, photographs, artifacts and portraits.

Celebrating these thirty years of Quarterly News, we feel it is an appropriate time to speak of Mary Beecher Longyear, the woman who saw the necessity of collecting and preserving a record of Mary Baker Eddy’s life. (Mrs. Longyear’s collection, in fact, continues to grow through generous donations of items from members and friends of the Longyear Museum.)

You as an eminent Christian Scientist can do much in educating others materially or scholastically.

— Mary Baker Eddy in a letter to Mary Beecher Longyear, Jan. 11, 1906

Mrs. Longyear and Christian Science

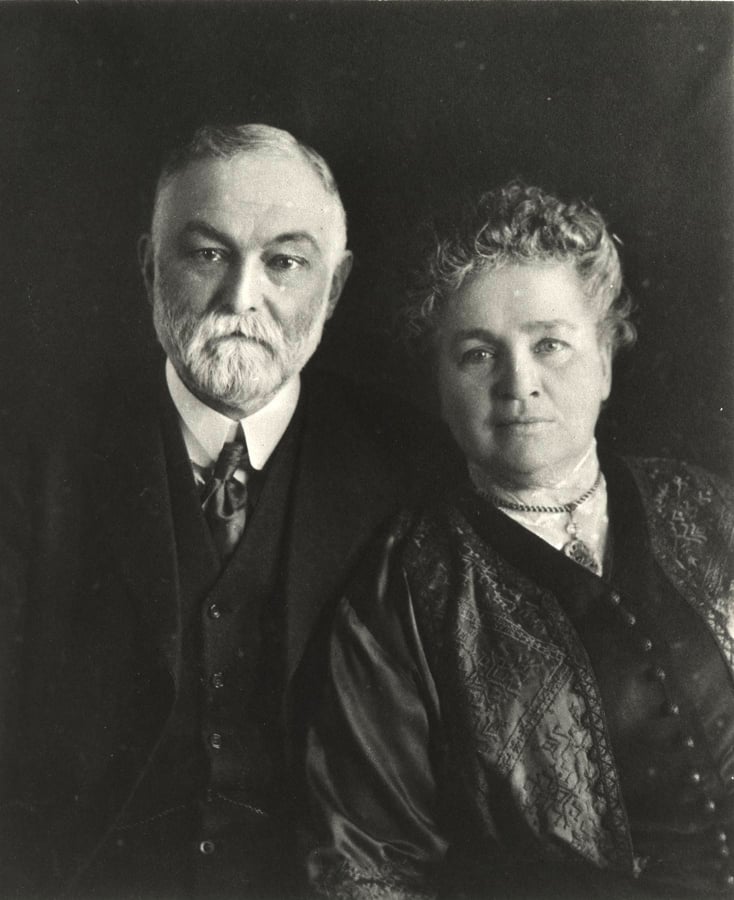

Mary Hawley Beecher was born December 21, 1851, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Caroline Matilda Walker and Samuel Peck Beecher. She was a twin in a family of seven children. Speaking of her ancestry in her autobiography, she comments: “We were somewhat proud of our name Beecher and had imbibed the idea that our grandfather Marcus Lyman Beecher…and Henry Ward Beecher’s grandfather were…cousins.” She also makes another statement in that same autobiography that her father was…a distant relative of the noted Henry Ward Beecher.”1 Mary’s childhood was spent in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and at the close of the Civil War the family moved to Augusta, Michigan. In her teens Mary studied to be a schoolteacher and moved to Marquette, Michigan, in 1877 to pursue her profession. There she met John Munro Longyear,2 who was working as “landlooker” reporting on the natural resources of lands ceded by the Federal Government to the Sault Ste. Marie Canal Company. Mary and John were married in Battle Creek, Michigan on January 4, 1879, and made their home in Marquette. They had seven children, three girls and four boys.

Early in the 1890s Mrs. Longyear was introduced to Christian Science while struggling with grief over the sudden death of an infant son. She became a dedicated student, had Christian Science Primary class instruction with Mary E. Crawford, and in 1894 joined The Mother Church (The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts). Nine years later she had Normal class with Edward A. Kimball under The Christian Science Board of Education, and received the degree of C.S.B.3 Mrs. Longyear was active on various church committees, contributed poems and articles to the Christian Science Sentinel,4 and for many years following the Longyears’ move to Brookline Massachusetts, enjoyed teaching the older children in The Mother Church Sunday School.5

Mrs. Longyear’s Contacts with Mary Baker Eddy

At first the only contact Mrs. Longyear had with Mrs. Eddy was through correspondence, which began in 1895 when Mrs. Longyear, wintering in France, wrote requesting permission of Mrs. Eddy to have Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures translated into French. Mrs. Eddy gave her permission, but the effort was not successful. Some years later Mrs. Longyear wrote of this experience, “You can imagine that the effort was not a success, as the man I employed to translate it [Science and Health] had never heard of Science before and I knew very little regarding its theory.”6

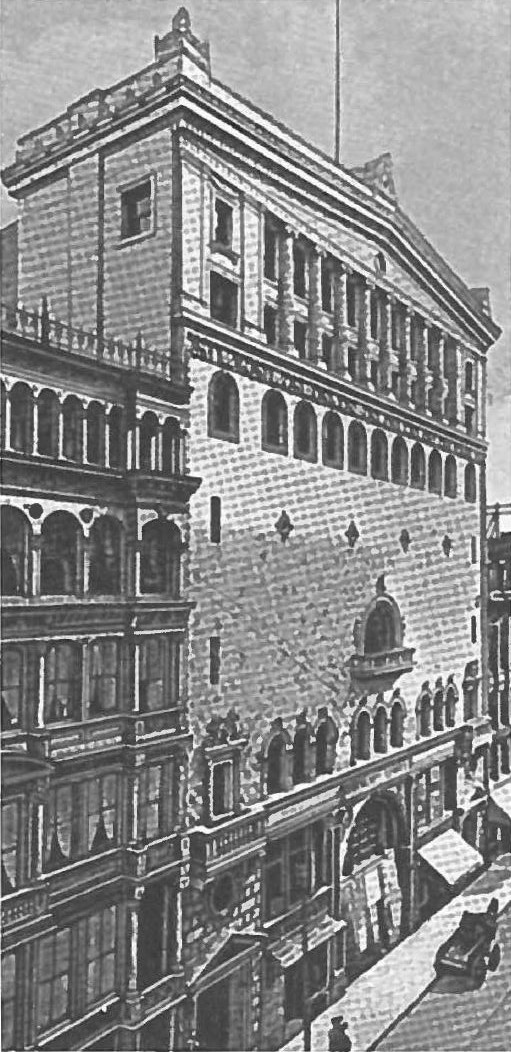

During the years 1899 and 1900 the Longyear family lived, temporarily, in Boston while the children attended schools in the New England area. Mrs. Longyear was quite busy with her family at that time and never thought of pursuing a meeting with Mrs. Eddy, but did see her when she spoke at the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church held at Tremont Temple on June 6, 1899. As Mrs. Longyear explains, “I knew that her time was fully occupied and I had no curiosity to see her personally, or to gain any help from her physical appearance. I saw her first when she appeared in Tremont Temple, but was not impressed. My greatest desire was to bring harmony and peace in my own home through the understanding of Christian Science and I knew that in order to gain that I must study her books.”7

When Mr. and Mrs. Longyear visited the Paris Exposition in 1900, Mrs. Longyear conceived the idea of displaying Christian Science literature in the Exposition. She wrote to Mrs. Eddy about it and received a note with her permission and blessing.8 According to Mrs. Longyear the response from the French public at the Exposition far exceeded expectations, and may have contributed to Mrs. Eddy being officially recognized for her distinguished activity in the writing and publishing of Christian Science literature by the French Government, who bestowed upon her the decoration of Officier d’Academie in 1907.9

The exchange of letters between Mrs. Longyear and Mrs. Eddy continued, covering many topics. Sometimes Mrs. Eddy would write requesting Mrs. Longyear’s assistance,10 and at other times Mrs. Longyear would discuss ideas with Mrs. Eddy. For example, Mrs. Longyear considered (in 1905), at Mrs. Eddy’s suggestion, establishing a school or university for scholastic education in the South. As was frequently the case, Mrs. Eddy continued to consider this idea and went the next step in clarifying and defining the real need. Mrs. Eddy wrote Mrs. Longyear, on January 15, 190[6], “I propose that the institution you found be called Sanatorium…that it be a resort for invalids without homes or relatives available in time of need; where they can go and recruit.”11 (For more of this letter and additional details see: Christian Science Sentinel, Vol. 19, No. 6, October 7, 1916, p. 110.)

Mrs. Eddy’s evaluation of the unselfish nature of Mrs. Longyear’s benevolence is expressed in a “Card” which was published in the Christian Science Sentinel, July 14, 1906. In that “Card” Mrs. Eddy stated regarding Mrs. Longyear’s charity: “Seldom have I seen such individual, impartial giving as this.”12

In June, 1905 at Mrs. Eddy’s invitation, Mrs. Longyear visited her at her Pleasant View home in Concord, New Hampshire. “We took a carriage and reached Concord at 2.00 as Laura [Sargent] had invited us. She met us at the door with the glad news that Mrs. Eddy would see us. I prayed to see with spiritual eyes[.] A vision of beauty tall and graceful appeared in the doorway[,] a beautiful white mantle[,] a white bonnet with a pink rose in it[,] long white strings[,] a cameo brooch[,] a black grenadine dress[,] daintily gloved hands[.] I will not write what she said[;] I never can forget it.”13 After Mrs. Eddy left for her drive, Mrs. Longyear visited with Mrs. Laura Sargent with whom a continuing friendship was begun. The following February Mrs. Eddy requested Mrs. Longyear visit her again; this time to discuss a business transaction.14 Apparently, it was after this February 1906 interview that Mrs. Sargent commented, “What in the world were you talking about that made Mother laugh so heartily? I haven’t heard her laugh like that since I don’t know when!”15

In her diary Mrs. Longyear mentions meeting Mrs. Eddy while out driving in September of 1909,16 and in January 1910 she was invited to lunch at Mrs. Eddy’s home in Chestnut Hill. Of this later meeting she wrote, “I take time to realize the blessing I had today. Went to Mrs. Eddy’s house to lunch and had a lovely visit with her. The greatest blessing on earth. The bright, joyful face of Mrs. Eddy greeted me. She kissed and welcomed me…she asked me if I knew the reason she liked to have me visit her. When I answered in the negative, she said, ‘It is because you give me nothing to meet.’ She said she often thought of me and asked me to think of her.”17

In July 1910 Mrs. Longyear received another invitation to visit the household. “Blest Christmas Morn. How Good is. Saw the loved household at Chestnut Hill and brought them gifts and had the supreme joy of Life in seeing Mrs. Eddy and kissing her and laughing with her.”18

Collecting the History of Mrs. Eddy’s Life and Work

It was in that same month that The Christian Science Board of Directors gave Mrs. Eddy’s grandmother’s spinning wheel to Mrs. Longyear.19 And in the following year, 1911, she bought one of Luella Varney Serrao’s sculpted marble busts of Mrs. Eddy.20 But it wasn’t until November 1917 that Mrs. Longyear was convinced that the history of Mrs. Eddy’s life and the early Christian Science movement should be preserved. She carefully searched Mrs. Eddy’s writings for any reference to history. Upon reading the following quote in Miscellaneous Writings — “Christian Science and Christian Scientists will, must have a history”21 — Mrs. Longyear decided she should act on the idea. She comments in her diary, “The history of Christian Scientists and the establishing of the church must be written so that no one in the centuries to come could doubt that Mary Baker Eddy and her faithful followers founded [T]he First [C]hurch of Christ, Scientist.”22

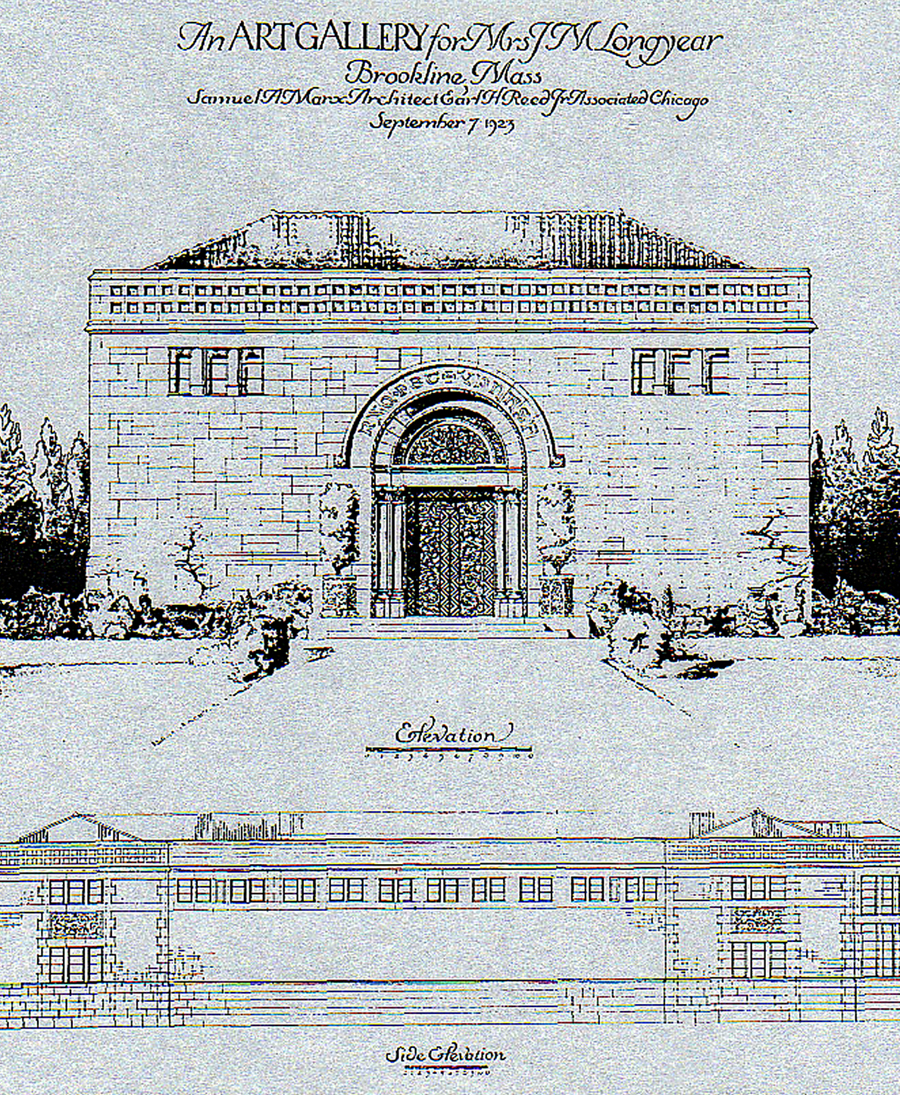

Subsequently, Mrs. Longyear wrote to The Christian Science Board of Directors and received permission to construct a building in which to house historic data on Mary Baker Eddy and Christian Science. She and her husband then met with the Directors on November 30, 1917.23 Since it was the feeling of the Board that any such building should be near The Mother Church, Mrs. Longyear bought land adjacent to the edifice, and in April of 1918 offered it to the Directors.24

She then began speaking with Mrs. Eddy’s students, sharing with them her thoughts about preserving a record of Mrs. Eddy’s life. Most of them agreed with her and were eager to help, but when asked to write their recollections and experiences some felt that Science and Health eliminated any need for personal reminiscences. In response Mrs. Longyear said, “…it was to preserve for all time the transparency of Mrs. Eddy’s character that the world might have refutation in ages to come if error would begin to belittle it as it constantly does now or tries to do.”25

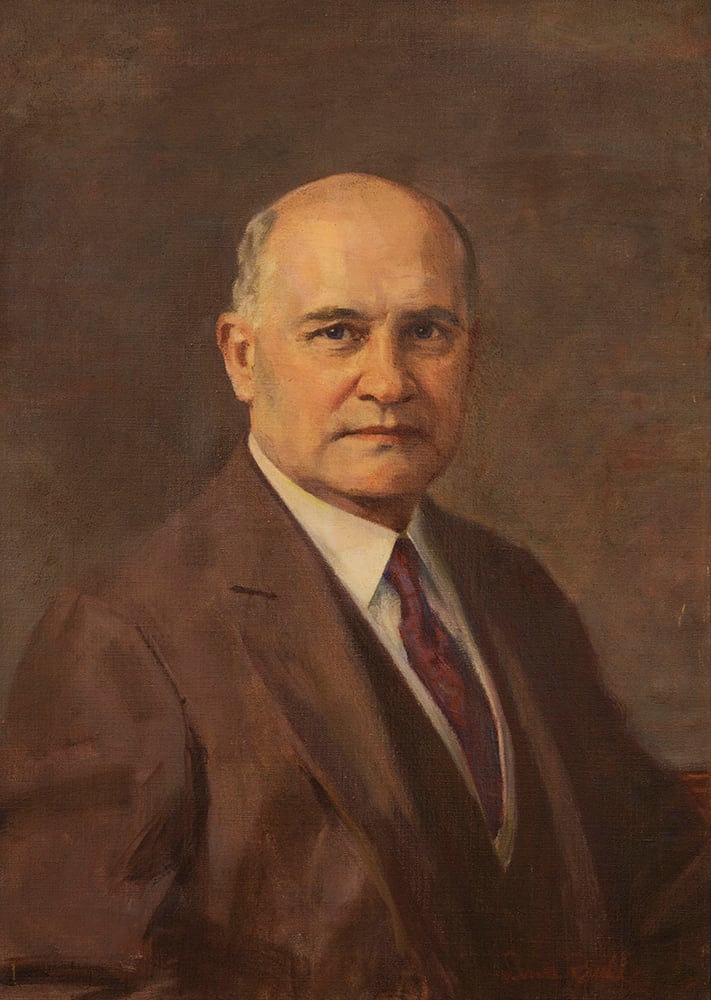

After arranging for photographs to be taken of early workers, Mrs. Longyear commissioned portraits to be painted, especially of those students of Mary Baker Eddy who had the advance designations of C.S.B. and C.S.D.26 At the same time she requested that these students write their reminiscences of their introductions to Christian Science and memories of Mrs. Eddy, feeling that these would be of great interest to future generations in showing how the dedication and support of such workers aided in the establishment of the early Christian Science Church.

Meanwhile, on November 11, 1918, The Christian Science Board of Directors wrote to Mrs. Longyear asking that she “…excuse them from giving any commission or official endorsement…” to her effort to collect historical material.27 In her diary Mrs. Longyear comments, “Well that is all right they do not object to my doing so. I am not disappointed. God my God will lead me and will not let me make mistakes.”28 Thus Mrs. Longyear felt free to follow the task before her — a vision that seemed to be uniquely hers. No doubt, this feeling was reinforced by letters such as one dated October 2, 1918, to Mrs. Longyear from Adam H. Dickey, member of The Christian Science Board of Directors, in which he remarked:

I just wish to drop you a line personally and tell you that I am glad to know that the differences existing between yourself and our Board of Directors are in a fairway to be adjusted. …I have not changed my opinion on any of the essentials of the work you are performing and I know that sometime it will be done, and in the right way.

The “differences” between Mrs. Longyear and The Christian Science Board of Directors were a complex matter with many facts not easily disentangled. The first fact was that Mrs. Longyear, the Board of Directors, and Board member John V. Dittemore were all vigorously involved in collecting documentation regarding Mary Baker Eddy’s life and the early history of her church. This collecting was complicated by the fact that all parties had engaged the same rare book/manuscript dealer to gather materials for them — a Mr. A. A. Beauchamp. Added to this mix was Mrs. Longyear’s friendship with John V. Dittemore. (Dittemore, due to a conflict of viewpoint with the rest of the Board, was eventually dismissed as a member of The Christian Science Board of Directors on March 17, 1919.)

Also, all this occurred prior to the establishment of a code of ethics in the field of preservation.29 It was a time in which, like many of his contemporaries, Mr. Dittemore could feel perfectly at ease in continuing to add to a personal collection of historical materials despite what we today so clearly see as a conflict of interest relating to his position as a church officer (from May 31, 1909–March 17, 1919). Mrs. Longyear began purchasing materials from Mr. Dittemore’s personal collection in 1919. Hence, the criticism for how a part of Mrs. Longyear’s collection came to her was articulated by church workers such as Judge Clifford P. Smith who wrote heron May 12, 1924: “Since the beginning of the litigation in March 1919…it is generally believed that you are or were one of his [John V. Dittemore’s] most ardent supporters and his chief contributor.”