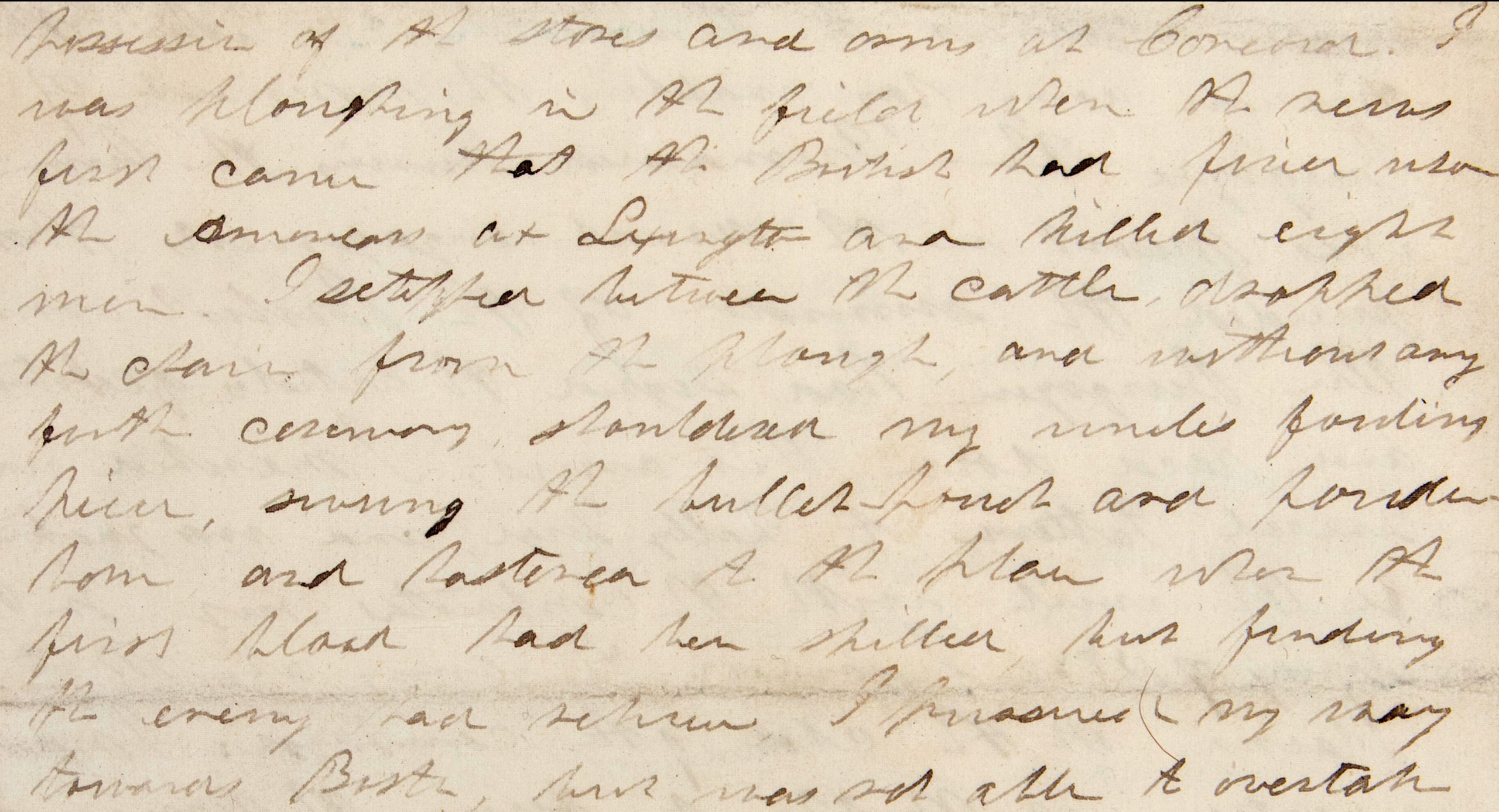

“I was ploughing in the field when the news first came that the British had fired upon the Americans at Lexington and killed eight men. I stepped between the cattle, dropped the chains from the plough, and without any further ceremony, shouldered my uncle’s fowling piece, swung the bullet-pouch and powderhorn and hastened to the place where the first blood had been spilled, but finding the enemy had retired, I pursued my way towards Boston. . . .” 1

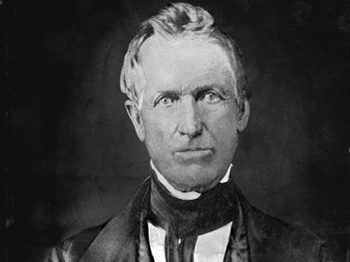

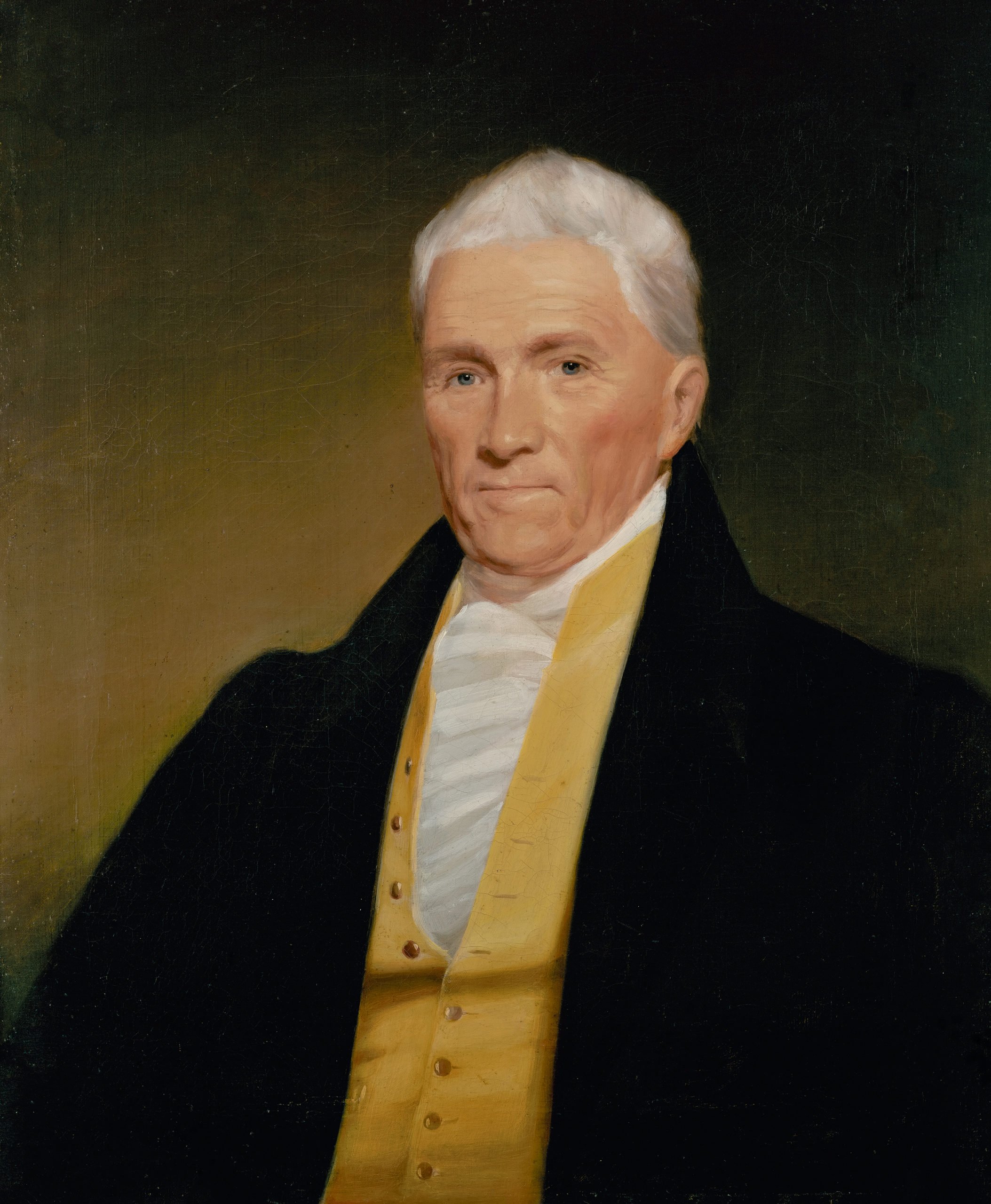

With this stirring eyewitness account, Gen. Benjamin Pierce related the events of April 19, 1775—the start of the Revolutionary War—more than 50 years later to Albert Baker, Mary Baker Eddy’s older brother. Young Benjamin had started that momentous day as a 17-year-old helping his uncle on the family farm in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, where he had lived since his father’s passing when he was six. By the next day, he had enlisted in Capt. John Ford’s company in Cambridge.

General Pierce’s subsequent recounting of battles spans the nearly nine-year war: He served in the battle of Breed’s Hill (Bunker Hill), witnessed from Dorchester Heights as the British evacuated Boston, and fought at Ticonderoga. In 1777, during a turning-point battle at Bemis Heights, he boldly dove into the smoke between the front lines and saved his regiment’s flag from being seized by the enemy.2 He also spent the winter with George Washington’s army at Valley Forge.

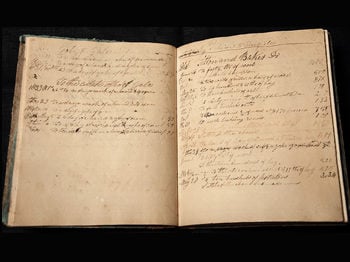

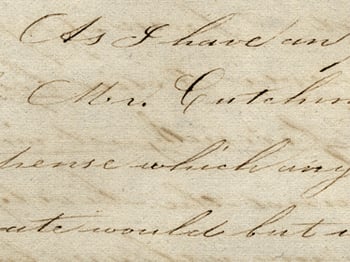

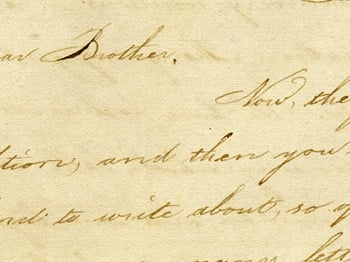

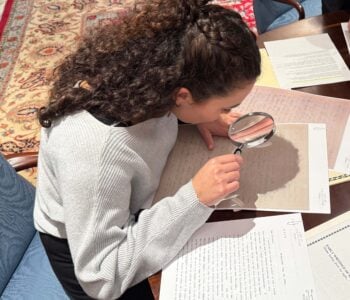

Benjamin Pierce—a friend of the Baker family patriarch, Mark—dictated a partial autobiography to Albert Baker, and the document is part of Longyear Museum’s collection. The unique Baker collection, including manuscripts, letters, artifacts, and photographs, sheds light on the family and the times in which they lived.

Mary Baker Eddy grew up with a keen sense of the bravery and sacrifice expressed by patriots who fought for American independence. She would later draw on these examples as Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science—pioneering a wholly spiritual way of demonstrating liberty, justice, and self-government.

In her most important book, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, she wrote this call to freedom: “Christian Science raises the standard of liberty and cries: ‘Follow me! Escape from the bondage of sickness, sin, and death!’ Jesus marked out the way. Citizens of the world, accept the ‘glorious liberty of the children of God,’ and be free! This is your divine right.”3

After the American Revolution, General Pierce headed north to work as an agent for a landholder in New Hampshire. The Continental certificates, paper currency issued by the Continental Congress he had earned as a soldier, were not worth much, but they were enough to buy a log hut and some land in Hillsborough.4 He began cutting and clearing away trees there in 1786. Described as having “bright, merry eyes,” he was “much beloved by the locals as an honest man of principle with a generous heart.”5

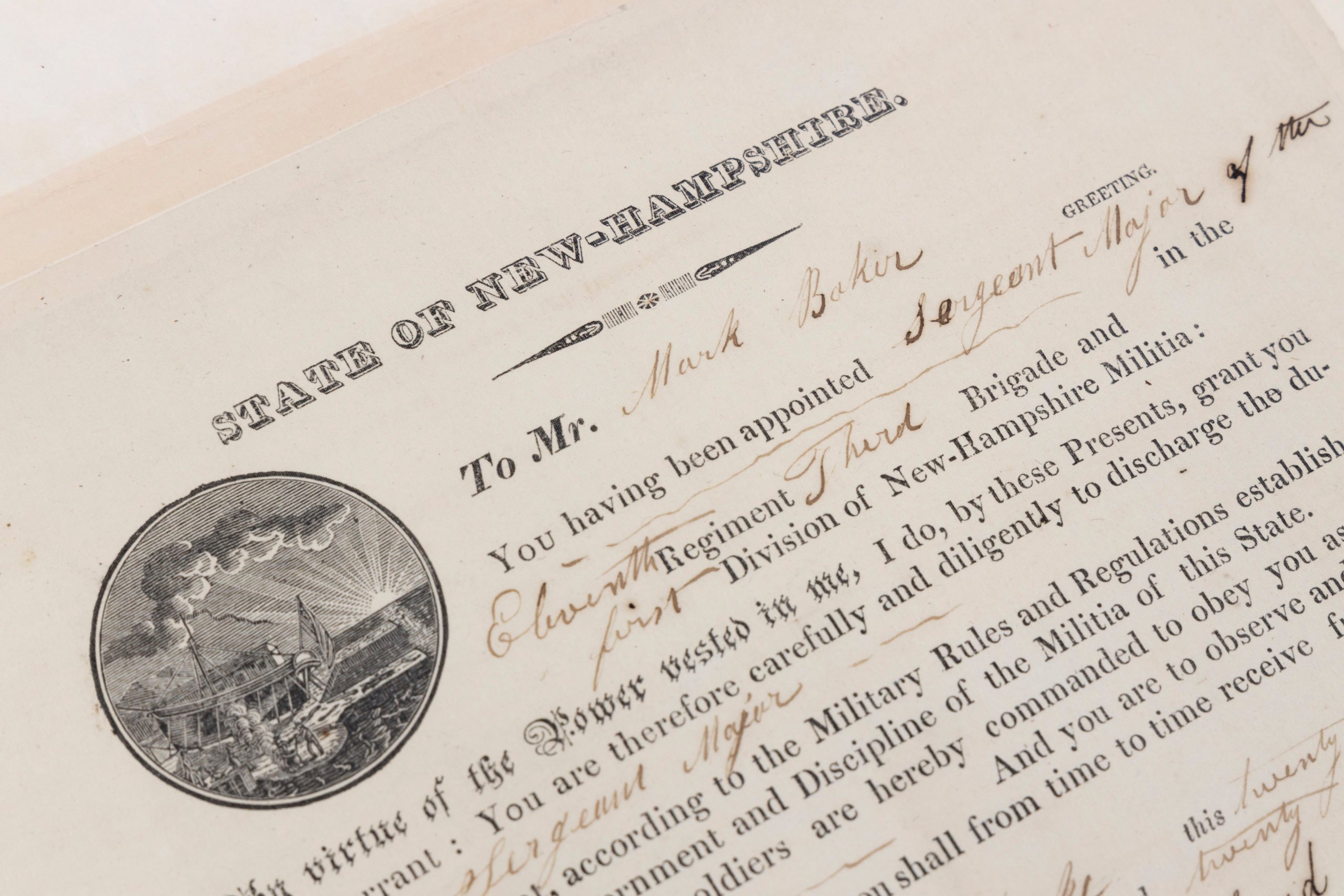

General Pierce joined the New Hampshire Militia and served for 21 years, attaining the rank of brigadier general.6 Mary and Albert’s father, Mark Baker, also served in the militia. The two were good friends, and the general was known to have been a frequent visitor to the Baker home in Bow, about 30 miles east of Hillsborough.7

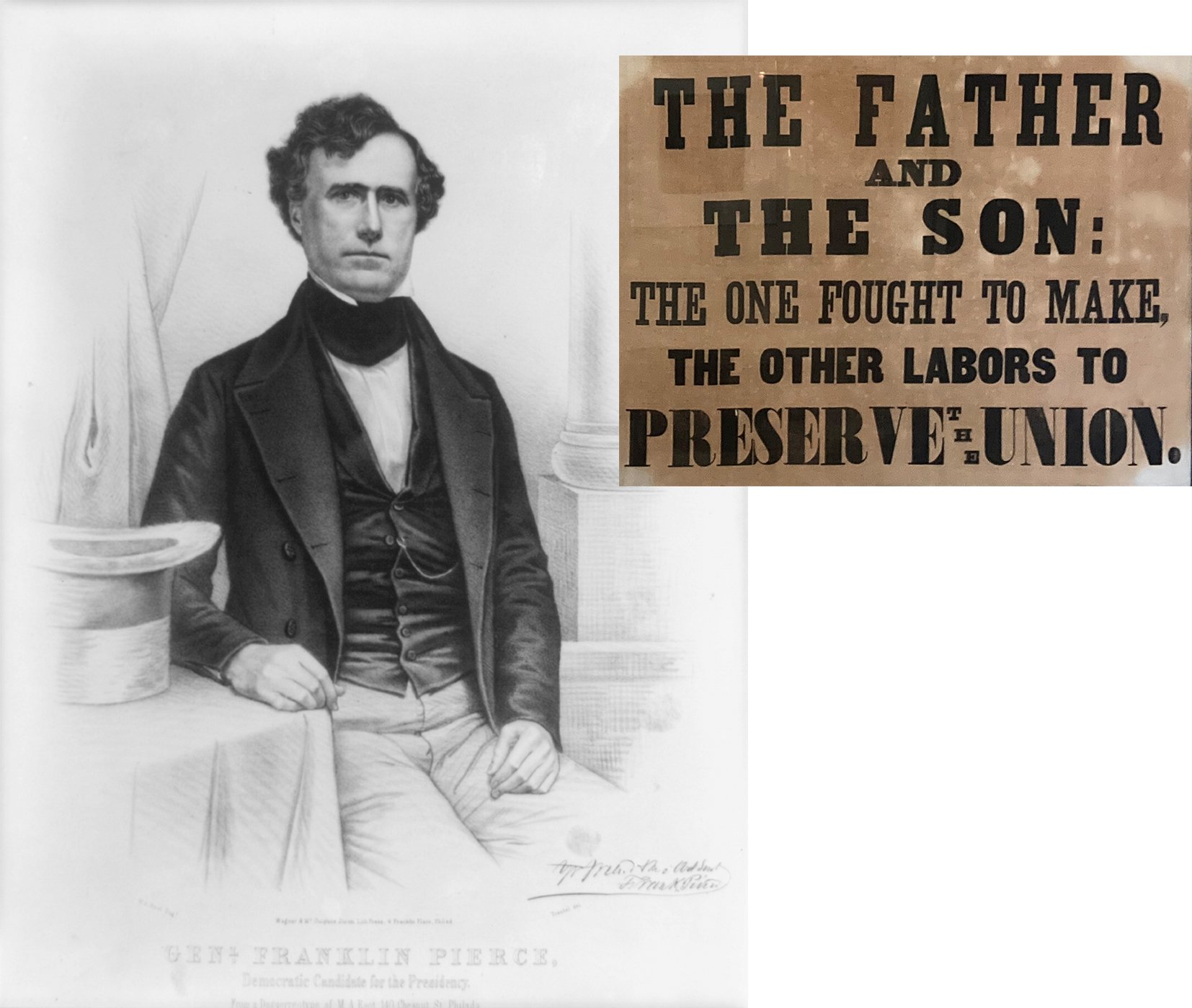

Mary was still in primary school when Benjamin Pierce served two one-year terms as governor of New Hampshire in 1827 and 1829. He was a Jacksonian Democrat—part of the common-man party the Bakers favored. General Pierce came to Concord to start his governorship wearing a tricorn hat as the symbol of the Revolution.8 In 1833, when President Andrew Jackson visited, the Bakers could have watched as the honored procession, accompanied by Governor Pierce, passed by their homestead in Bow.9

The following year, in 1834, Albert graduated from Dartmouth College and began boarding with Pierce and his wife, Anna, at the elegant Hillsborough home they had built 30 years before, complete with an upstairs ballroom.10

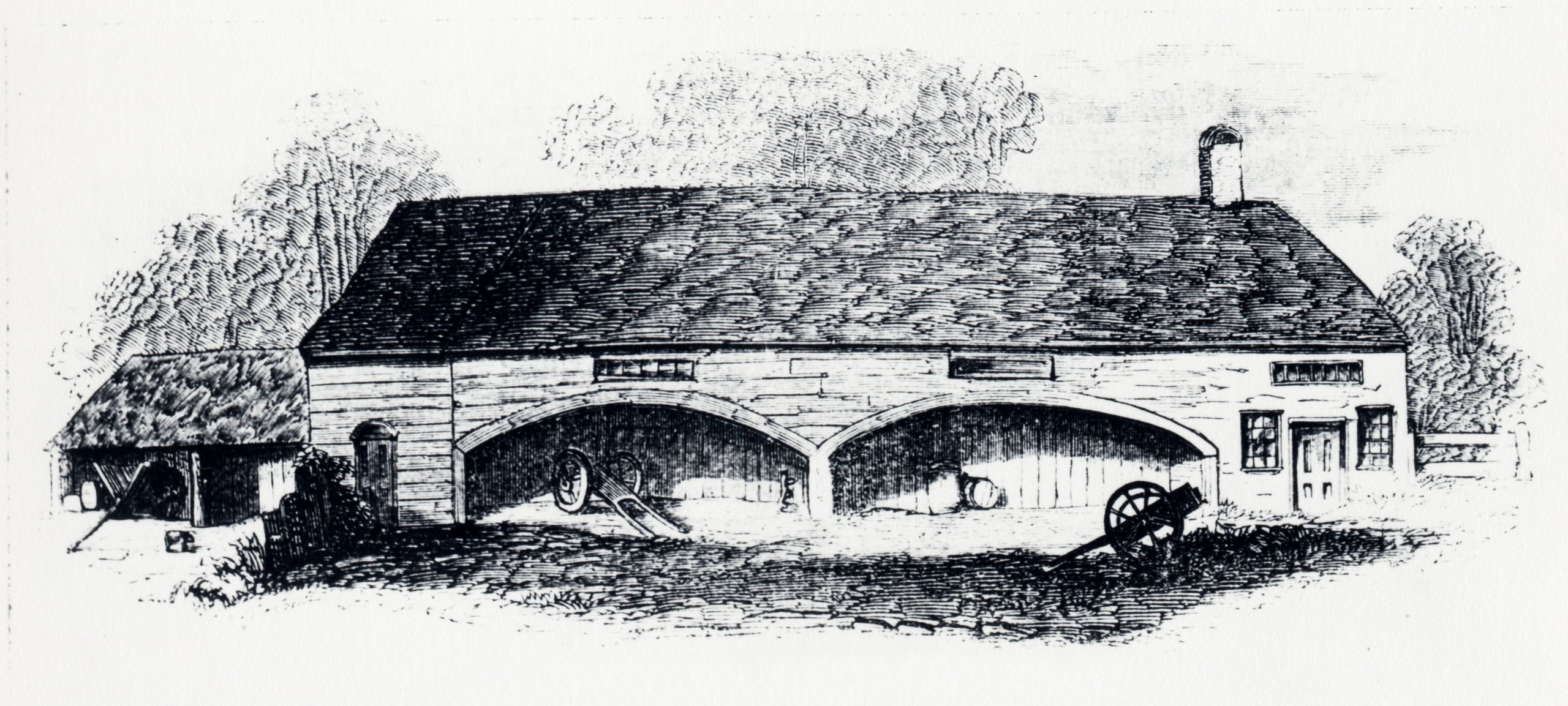

Albert studied law with Governor Pierce’s son Franklin across the street in an office converted from a horse shed.11 By this time, Franklin was already successful in politics in addition to practicing law. During his stay with the Pierces, Albert also spent some time teaching at Hillsborough Academy, a local secondary school, to help pay his expenses.12

After further preparation with a lawyer in Boston, Albert was admitted to the bar and returned to the Pierce home in Hillsborough in 1837.13 There, he carried on Franklin’s law practice and watched over the elderly general and his wife while Franklin served as a U.S. Senator in Washington.14

Benjamin Pierce wrote to Mark Baker in the spring of 1838, commenting not only on Albert’s talents, but also on the potential of his younger brother, George, who had come for a brief visit: “Sir your son the lawyer . . . [is] a young man of . . . correct habbits & gentlemanly deportment, a strict attendant of public worship when his health will admit.” Of the younger brother he wrote, “I think him a young gentleman of fine tallents well informed & of much promise.”15

Franklin Pierce’s solicitude for his parents’ well-being, and his strong reliance on Albert, characterize the correspondence between the two men. When Franklin received news of the death of his mother in December 1838, he wrote to Albert: “Do pass all the time you can with my dear father & omit nothing which will contribute to his comfort. . . .”16

Benjamin Pierce’s own letters to relatives and friends in his later years show how much his patriotic fervor still motivated him. For example, in 1838 he wrote to John Wingate Weeks, a former Congressman and fellow Jacksonian: “My heart is full of warm Desire that the Country that Was purchased by Toil privation & the afusion of Blood Should [not] be Disposed of for a [less] price. . . .”17

Governor Pierce was well known for keeping memories of the Revolutionary War alive. On Christmas day 1824, he had hosted a gathering of fellow veterans of the war at his home—along the route between Keene and Concord.18 The men enjoyed a meal and gave speeches, praising the values that had enabled the nation to prosper. In notes for a toast, the general described April 19, 1775, as “the first flash of the American true fire, which never ceased to blaze till she was acknowledged free and independent.”19

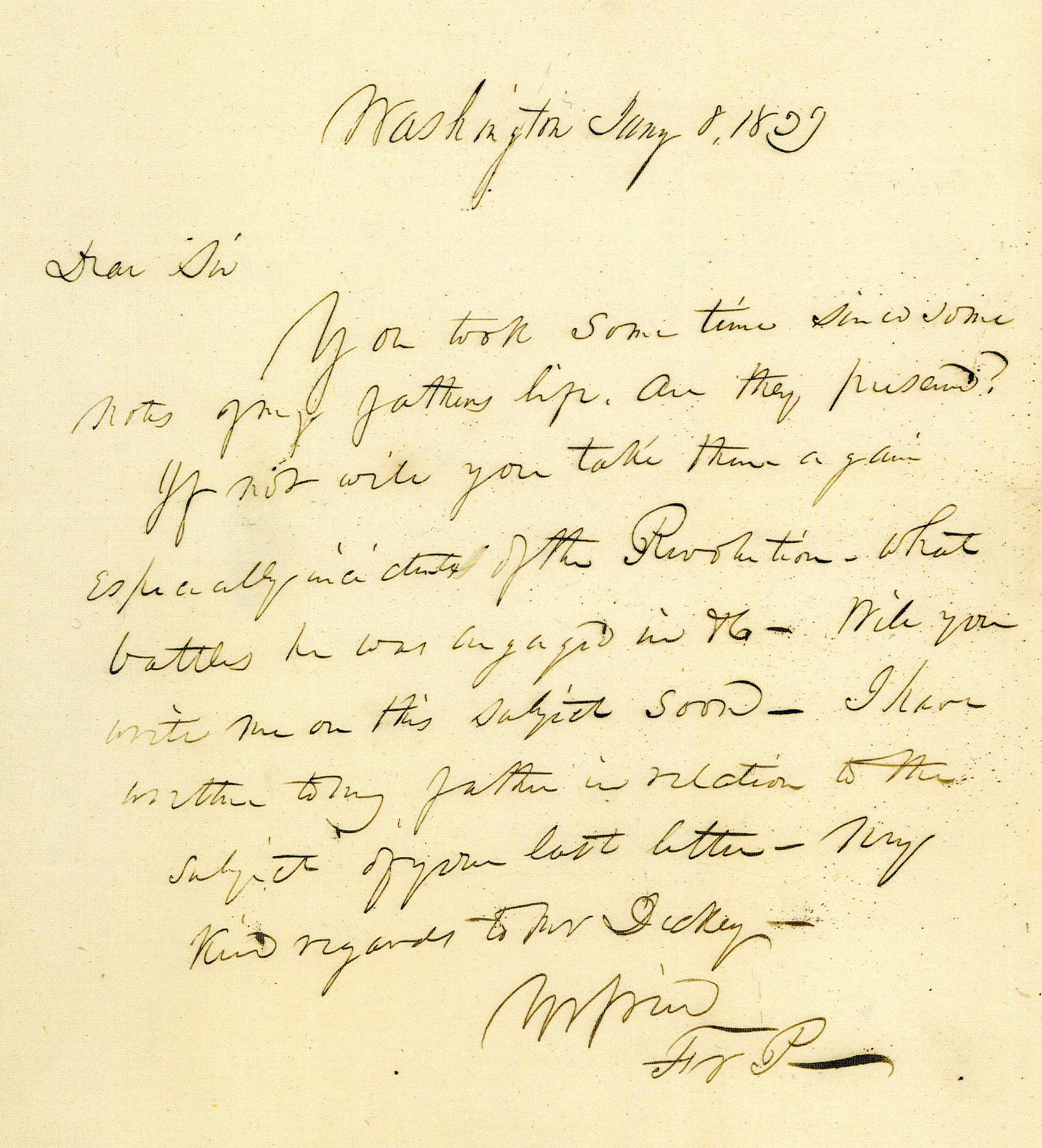

In January 1839, Franklin wrote Albert, asking about notes he had taken of his father’s recollections: “Are they preserved? If not, will you take them again, especially incidents of the Revolution—what battles he was engaged in. . . .”20

While Albert did record the elder Pierce’s memories, he apparently was not keeping up with Franklin’s appetite for news from the home front. Franklin often asked him to write more frequently.21 In one letter ending with such a request, Franklin wrote of his father: “He has been a truly extraordinary man. . . .”22

Albert also helped the general stay in close contact with his eldest daughter, Elizabeth, who was married to Gen. John McNeil, known for valor in the battles of Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane during the war of 1812.23 Albert had stayed with the McNeils and tutored their children when preparing for the bar in Boston.24

Albert’s career turned political but was cut short when he passed away in 1841. His friend and mentor Franklin Pierce reached the pinnacle of American politics when he was elected to serve one term as President of the United States, from 1853 to 1857.

Fanny McNeil Potter—the McNeils’ daughter and Franklin’s niece—filled in at times as a hostess at the White House.25 Fanny had known young Mary Baker when Albert worked with her uncle. During Mrs. Eddy’s visit to Washington at the beginning of 1882, Mrs. Potter escorted Mrs. Eddy to pray at the grave of General McNeil, and to visit the prison where President James Garfield’s assassin was being held.26

Mrs. Eddy drew upon her family’s connection to Benjamin Pierce in 1907, after an intense attack in the press. For example, to rebut a McClure’s Magazine account that depicted her father as gaunt and feeble, she wrote: “My father’s person was erect and robust. He never used a walking-stick. To illustrate: One time when my father was visiting Governor Pierce, President Franklin Pierce’s father, the governor handed him a gold-headed walking-stick as they were about to start for church. My father thanked the governor but declined to accept the stick, saying, ‘I never use a cane.’”27

At his funeral on April 3, 1839, hundreds of New Hampshire citizens paid their last respects to the general, a patriot who had served the public for more than 60 years.28 Among Benjamin Pierce’s last words, recorded by Albert, were messages of love for his children and a one-sentence summary based on a spirit of self-sacrifice: “In every battle I ever went into, I always held my life in readiness to be offered.”29

In her work to uplift humanity to a higher sense of freedom through Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy exemplified that spirit of self-sacrifice. She wrote: “All that I have written, taught, or lived, that is good, flowed through cross-bearing, self-forgetfulness, and my faith in the right. . . . In every age, the pioneer reformer must pass through a baptism of fire. But the faithful adherents of Truth have gone on rejoicing.”30

Next month: Mrs. Eddy’s own ancestors’ contributions to the Revolutionary War and her membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution.