Recent news reports in Boston of efforts to halt development of a property in Roslindale, Massachusetts, once owned by Mary Baker Eddy have prompted us to take a closer look at the time she spent living there.

In the winter of 1891, while living in Concord, New Hampshire, Mary Baker Eddy was once again looking for a home. And, as always, she was looking for God’s direction.

Two years earlier, in the spring of 1889, she had withdrawn from teaching a Normal Class at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College after just one day in the classroom, and left Boston and her home on Commonwealth Avenue. Seeking peace and quiet to pursue the work she felt God had given her to do, Mrs. Eddy stayed briefly in Barre, Vermont. Soon, however, the summer vacationers arrived, filling the town with their bustle and noise. She moved on to her native New Hampshire. In the city she called “dear, quaint old Concord,”1 Mrs. Eddy settled into a large rented house at 62 North State Street. In addition to her secretary Calvin Frye, her maid, and a cook, the household now also included a personal assistant: her student Laura Sargent.2

In a series of surprising moves over the next months, she closed her college in Boston, resigned the pastorate of her church, dismantled its organization, and transferred The Christian Science Journal to the National Christian Scientist Association. Then she plunged into a major restructuring of the Christian Science textbook, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. By the end of 1890, she had completed her revision, and in January 1891, 3,000 copies of the pivotal 50th edition were rolling off the presses in Cambridge, Massachusetts.3

As Mrs. Eddy worked, her rented house just blocks away from the state capitol was proving unsuited to what she most needed and yearned for — a home that could be both a base for her efforts for mankind and a retreat from mankind’s clamor. Should she, perhaps, relocate nearer her students in Boston, but in a place that provided seclusion for her work? During late fall and early winter, her student Ira Knapp and her recently adopted son Ebenezer Foster Eddy, whom she affectionately called “Benny,” searched for just such a property. At the start of 1891, an elegantly-designed house with spacious landscaped grounds became available across the street from the Knapp’s home in Roslindale on the outskirts of Boston. Mr. Knapp recommended it to Mrs. Eddy.4

She hesitated, waiting for some sense of God’s command. For one thing, she was concerned about how “Benny” and the sometimes hard-pressed secretary Calvin Frye might be affected by the turmoil of thought stirred up at her return to the center of the Christian Science movement. Not long before they left Boston, Calvin, struggling under the enormity of his duties, had collapsed and tumbled down a flight of stairs, where he was healed on the spot by Mrs. Eddy.5 Now she wrote Knapp:

If only I could be sure that my son and Mr. Frye would stand the fire upon them if I was there, I would go without another word…. If only I knew that Boston or the suburbs was the place that God wants me to go I would go without further counting the cost….?6

When she finally decided to move forward, Mrs. Eddy exhibited her usual practicality in business transactions. She instructed Knapp to tell the owner of 175 Poplar Street that $14,000 would be her best offer. “If he does not see fit to accept I shall be satisfied,” she wrote. “Our loving Father will direct.”7

When prolonged negotiations caused months of delay, she arranged for the house to be acquired through a third party, Knapp’s brother-in-law, Seth P. Stickney.8 A price of $17,000 was agreed on, and the house was vacated so that some alterations could be made.9 On May 23, 1891, Mrs. Eddy moved into her Roslindale home. It would prove to be a short stay.

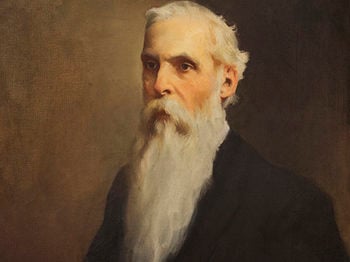

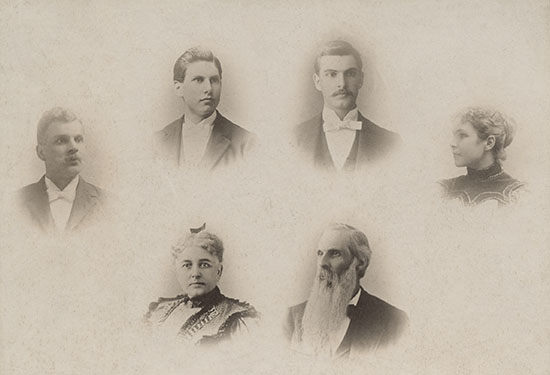

Her neighbors, Ira Knapp and his wife, Flavia, were both faithful workers who had been taught by her at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College. Several years earlier, they had entertained her at their former home in Lyman, New Hampshire, and thus were personal acquaintances as well.10 In 1892, Mrs. Eddy would appoint Ira as one of the first Directors of The Mother Church, and both Knapps would be appointed First Members after the church was reorganized that year.

A warm relationship developed between the two households. For example, Mrs. Eddy wanted access to a telephone, still a fairly recent invention, but did not want the disruptive device in her own house. So a phone was installed for her in the Knapp home. Presumably, Flavia or one of the Knapp children would run across the street with any messages, should the need arise.11

On a few occasions, Ira took Mrs. Eddy out on her daily drive. As she got to know him better, Mrs. Eddy became aware that Ira had developed what his son Bliss described as “an abnormal sense about celebrating birthdays.”12 Ira refused to celebrate them, perhaps rigidly considering them to be contrary to his Leader’s instruction: “Never record ages.”13 To correct this extreme posture, Mrs. Eddy decided to celebrate for him. On June 7, she sent a birthday present across the street to him: a vase filled with flowers, accompanied by her photograph in a hand-painted frame.

June 7 also happened to be Bliss’s birthday, so she sent him a present, too — her favorite canary in a fine brass cage. Mrs. Eddy also presented the Knapps’ daughter Daphne with a gift of two black-enameled bracelets which she herself had worn. Dropping in on the Knapps one afternoon afterwards, and receiving thanks all around for her gifts, Mrs. Eddy noted that Ralph Knapp was silent. It came to her that she had failed to send a present to him. As soon as she returned home, she sent Calvin Frye across the street with a beautiful small clock for Ralph.14

But for all these occasional neighborly pleasantries, Mrs. Eddy soon came to feel this was not the place God had intended for her. She summed up her experience in a letter to Laura Sargent:

I have no desire to live in the place of beauty that the Roslindale home is — a beauty unavailing in Christian Science. There is no retirement, no solitude, no quiet in it. It is a hillside decked with flowers and ornamental trees and shrubs and luxurious fruit and garden, but the walks are so steep I cannot follow them…. The whole site is surrounded with streets. The piazza goes all around the house, but from every side you are saluted with noise.15

These words help explain why, after less than a month, Mrs. Eddy abandoned her Roslindale house and returned to the rented house on North State Street in Concord, where she reported to one student:

The summer is cool, and the shade trees friendly … that is about all I can say of dear, kind, old Concord. Wherever we are, God is, and that is all I can hope for here.16

In the more peaceful solitude of the next few months, Mrs. Eddy produced Retrospection and Introspection, that deeply spiritual examination of her life as Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science and of its mission to humanity.

With that work finished and her church awaiting reorganization, she resumed looking for a home. Ira Knapp was again asked to aid in the search. But in late fall of 1891, Mrs. Eddy found it herself. During a drive on the outskirts of Concord, she passed a farmhouse on a hill that sloped away toward the distant uplands and pastures of her childhood at Bow. After rebuilding the structure to accommodate her needs and the needs of her household, she moved in the following June.17 Located on Pleasant Street, she named her new home accordingly “Pleasant View.” Here, over the next sixteen years, she would reorganize her church and guide its growth, write its Church Manual, continue to revise the Christian Science textbook, and against all her desires for peace and privacy, become one of the most newsworthy and talked-about women in America.

Through it all, Mrs. Eddy had bent to her sense of God’s purpose for her, seeking only to know “the place that God wants me to go.” As she told Ira Knapp, “I have longed for a home by the seaside, but now it seems that God has prepared one for me on a hillside.”18